It’s been about four months since the inland barge and towing industry began addressing the challenges of Covid-19, and lessons learned are already emerging that will likely influence operations well into the future.

Unlike many businesses that have been forced to shutter or greatly reduce operations, barges, towboats and tugboats continue to operate without interruption, moving commodities along the rivers, coasts and Great Lakes that have helped keep the economy humming.

As “essential, critical transportation workers,” inland mariners transport energy, agricultural and construction products, while also helping the pandemic response by guiding hospital ships into harbors and moving materials used to make medical supplies and hand sanitizers.

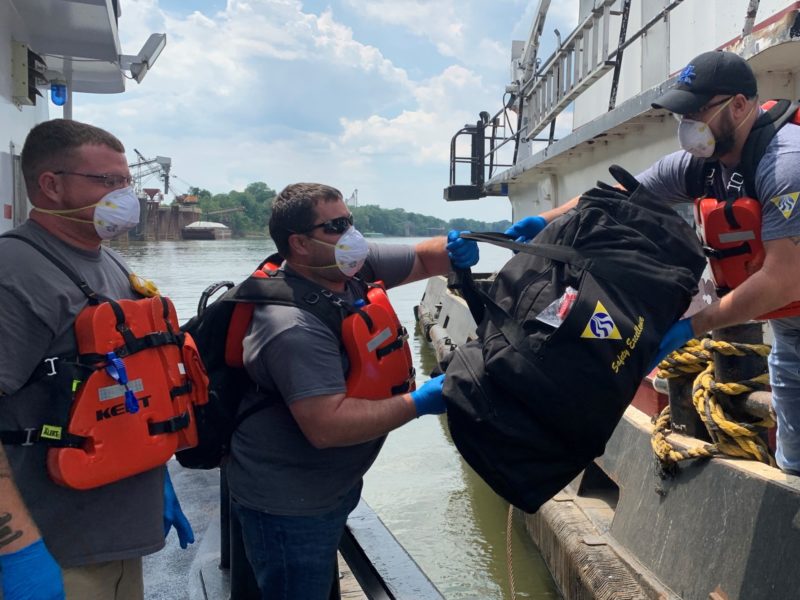

The barge industry has taken significant steps to protect its workers and vessels. Companies have activated emergency plans that are normally deployed during hurricanes or security incidents. They have launched safety and health protocols that are in line with state, local and federal guidelines, closed shoreside offices to work at home, invested in personal protective equipment and disinfectant materials, and implemented health screenings and new procedures for crew changes, vessel cleaning and mariner hygiene.

As a result, inland operators say, infections among workers have been minimal, companies have not laid off employees, and many continue to actively hire.

COVID-19 EFFECTS

But while the industry has continued operations, it has not totally escaped serious fallouts from the coronavirus pandemic. Many company officials report that implementing new health and safety protocols has been very expensive, and a global economic slowdown caused by the pandemic combined with declines in energy markets occurring before Covid-19, have deeply reduced the demand for their services.

“I contrast our experience with our colleagues in the cruise ship and the passenger vessel industries, where the lights just went off,” said Jennifer Carpenter, president and CEO of the American Waterways Operators, which represents the tugboat, towboat and barge industry. “For us, it was more of a dimmer switch. Everything is moving but there’s just less of it. Volumes are really down across the board.”

She said coal is down, not just due to Covid-19 but because coal plants have been closing and demand declined during a mild winter. Petroleum movements slumped because no one was flying or driving during the past few months due to business shutdowns. When auto plants shuttered, demand dropped for steel. Grain movements seems to be the only bright spot.

“We have seen an approximate 30 percent slowdown in upbound raw material inputs into the steel industry due to the slowdown in the auto and energy industries,” said Mark Knoy, president and CEO of American Commercial Barge Line, one of the nation’s largest barge companies. “We’ve also seen a significant slowdown in chemicals and refined products due to consumer reduction in gas, diesel and jet fuel.”

Carpenter calls it “demand disruption” that will affect companies differently depending on how diversified their business is, the debt load they are carrying, and their financial situation before Covid-19 hit. More consolidations are possible, she added. “I’m not hearing a lot of fear about the bottom dropping out. It’s more of not being able to predict a big positive recovery. We are still in a dimmer switch analogy. (A recovery) won’t be bright, but it won’t be black. It might be brighter in some areas, and elsewhere a little dimmer.”

Many companies, Carpenter added, have taken advantage of the Small Business Administration’s Paycheck Protection Program to help businesses struggling during the pandemic. This has prevented layoffs. But generally, the barge industry is not looking for Uncle Sam to send an infusion of funds their way, but rather to do things that help strengthen the industry like funding lock and dam improvements, supporting the Jones Act, and creating greater protections from coronavirus-related lawsuits.

While impacts of the pandemic continue to play out, the industry has begun to assess how adaptations made during the Covid-19 response might affect operations going forward. Many of the responses that companies have put into place out of necessity will likely become permanent because they have made operations more efficient and cost-effective, many say.

INCREASED TECHNOLOGY USE

Perhaps one of the biggest changes that could have staying power has been the move to digital communications. “A very positive lesson of this experience has been how successfully we’ve been able to leverage technology to get us through this,” Carpenter said.

Companies are relying on meeting apps to conduct daily business, as their shoreside offices have closed and people are working from home. With the encouragement of the Coast Guard, many are asking that audits, surveys and vessel inspections be done remotely, with companies supplying objective evidence, and inspectors “touring” vessels and meeting with crews by videoconference rather than on the boats.

AWO recently held its April board meetings virtually, instead of at a large Washington, D.C., hotel followed by lobbying visits with members of Congress. And instead of the annual summer visits in which lawmakers and their staffs come aboard inland vessels to learn about their operations, AWO is organizing “virtual tours.”

AWO doesn’t want to do away with live events, Carpenter said, but the success of videoconferencing could lead to more virtual events in the future. It can make meetings more accessible to those too busy or too far away to attend multiple-day conferences. “There’s a lot to think about, and I’m excited about having that conversation with our members and figuring out what the right balance is.”

Houston, Pa.-based Campbell Transportation Company Inc., which operates barges, towboats, four shipyards and fabrication shops along the Ohio and Monongahela rivers, is unsure if certain jobs could be done from home indefinitely, but the work-at-home experiment during the pandemic will make the company more flexible, according to Gary Statler, managing director, safety, regulatory compliance and HR. “If someone needs to work from home for whatever reason, we’ll be able to offer that to our employees more readily than we have before.”

Engagement within the company, which employs about 500, has been stronger because of technology. “It really is a different world,” Statler said, and running a company during the pandemic is much easier today than it would have been 10 years ago due to advances in technology.

Video calls with shoreside employees and mariners have become a normal part of operations now, added Peter Stephaich, CTC’s chairman and CEO, who also chairs the Waterways Council. “We’ve gotten used to it, it’s a normal thing.”

Remote work might not be for everyone, however, but it’s still important to be able to do it when necessary. “Our industry is different,” Carpenter said. “People need to be on boats, and you won’t have remote shipyards. But I think some companies will look at it for shoreside employees and there will be a continuum as they realize the possibility to save real estate costs. But other companies will say this isn’t for us, but it’s good to know that we can do it when we have to.”

At ACBL, Knoy said his company has always had remote work and is comfortable using remote technologies. Today 85% of the workforce works remotely on boats, fleets and terminals, while many customer service employees work from home. “We expect about 20-30 percent of traditional office teammates will continue to work remotely going forward,” he said.

Use of technology to perform remote inspections, audits and surveys is also becoming more common. The Coast Guard is encouraging the practice and both federal inspectors and private inspection companies are tooling up to do remote vessel and facility visits.

Remote inspections have many advantages, such as allowing inspectors to reach vessels that are in isolated locations more quickly, while also reducing vessel downtime. During the pandemic, remote technologies are safer for both inspectors and crewmembers by minimizing close contact, while also helping companies meet inspection deadlines, especially the upcoming Subchapter M compliance deadline in July.

No one believes that remote inspections will permanently replace in-person visits, as there are definite plusses in having an inspector meet face-to-face with the crew and walk around a vessel. But there could be circumstances in which remote reviews are preferable and just as effective. Creating a mix of remote and in-person inspections and using technologies like drones should be explored further, Carpenter and others said.

OTHER CHANGES

Another pandemic approach that could be used in the future is telemedicine. Companies have relied on this increasingly to screen mariners and shoreside employees for the virus and analyze symptoms. Carpenter thinks this could be a helpful, long-term tool for keeping mariners healthy, especially during the flu season now that companies have experience dealing with the coronavirus that presents similar symptoms.

“Companies have developed relationships with telemedicine providers, and what a great thing that is for an industry where you’re going to be on a boat for two to three weeks at a time,” she said. “We would be able to ramp up and deal with seasonal challenges like the flu just like we plan for high or low water. I think we’ll see long-term incremental change and improvements in how we manage health and safety going forward even after the Covid period.”

Statler of Campbell Transportation added that companies will also become more focused on worker hygiene and cleaning practices. “Our cleaning practices to make sure things are sterilized, those best practices will continue on,” he said. “And we’ll be more sensitive to someone not feeling well and not overlook that,” as both companies and employees are far more aware of the threats of contagion and the need to isolate when ill.

The industry’s vast experience with contingency planning, safety management systems and incident command structures that are used during hurricanes, unusual water conditions and security incidents have helped barge companies deal with the challenges posed by the pandemic, Carpenter said.

“This is a resilient industry. Companies have had to work quickly to adapt to a snowballing situation and they did so without missing much of a beat operationally,” she said. “That came from experience ... Some folks had pandemic plans and were able to activate and improve on them as Covid ramped up, while others didn’t have pandemic plans but had emergency response plans that they modified to respond to this situation.”

ACBL’s Knoy said his company constantly prepares for emergencies and these skills and policies have been helpful during the pandemic. “The only difference in this emergency plan and practice is the invisible part of it (the virus). Otherwise, preparation, planned practices and exercises keep us prepared.”

He said he expects that lessons from the pandemic will lead to further refinements in ACBL’s existing response plans.

Going forward, the spike in new cases in late June will require inland companies to keep even closer tabs on the health of their workers.

There is no vaccine and “we’ll be dealing with this for a long time, so we can’t let our guard down,” said Carpenter. “We must continue with testing and social distancing because crewmembers’ health and safety is the linchpin of our operation.”