Potential impacts on fishing, property values and tourism loomed large among critics of the Atlantic Shores offshore wind project during a virtual public hearing held by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management.

The online proceedings during more than five hours Monday pitted those views against project supporters, who focused on climate change and how it will affect the densely populated New Jersey coastline.

BOEM’s draft environmental assessment for the Atlantic Shores project off Atlantic City runs over 6,000 pages. Opponents are asking the agency to extend a 45-day public comment period past July 3, insisting the public needs more time to understand the proposal and its implications.

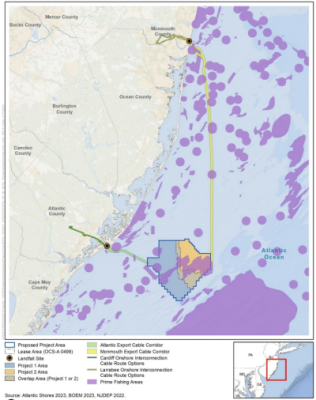

With turbines standing 574 feet above sea level at their rotor hubs and 1,047 feet high at the blade tips, the future visual impact – amply illustrated by simulated images in the DEIS document – is alarming seaside homeowners and the tourism industry.

“Frankly, all of us have bought a view,” said homeowner Paul Snyderman. “Everyone living at or near the shore has made an investment.”

BOEM workers said the DEIS document notes alternatives to reduce the visual impacts seen from shore. Removing 31 turbines from the array would move the first visible machines out from 8.7 nautical miles offshore to 12.75 miles, for example. Those options include restricting the height of turbines to 522 feet at the hubs and 932 feet at the blade tips.

Other alternatives in the DEIS would lessen impacts on fish habitat. Removing up to 16 turbines and one offshore power substation from the array would buffer the locally named Lobster Hole, and moving 13 turbines could widen space around sandy ridges on the sea floor, the document says. BOEM workers said “micro siting,” shifting the installations elsewhere in the array design, could accomplish that too.

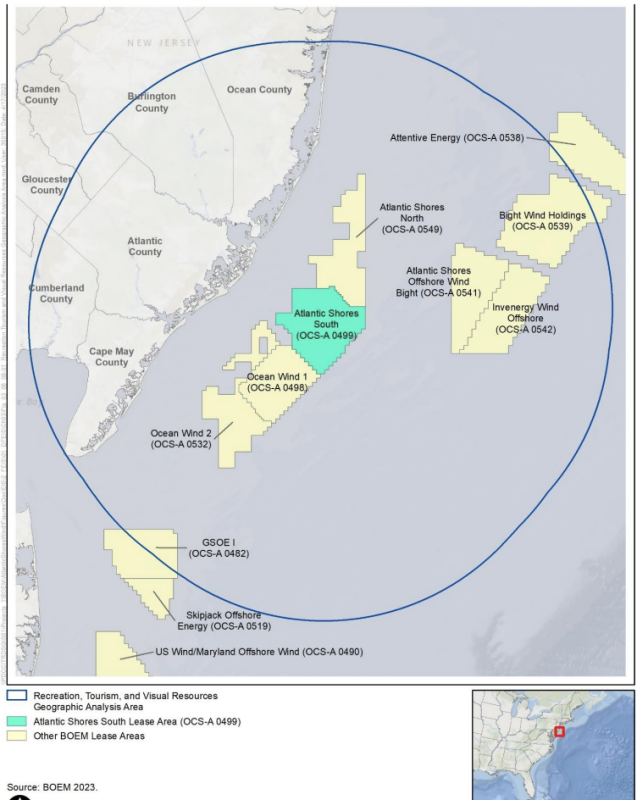

A possible buffer zone, suggested by fishermen and other mariners, could separate the Atlantic Shores lease from the neighboring Ocean Wind 1 project. The DEIS considers a corridor 0.81 nautical miles to 1.08 nm, running roughly southeast to northwest between the tracts, east of Atlantic City. That could involve moving the locations of four to five Atlantic Shores turbines, the document says.

The Atlantic Shores plan would cover some 885 acres of natural sandy bottom – habitat for scallops and surf clams – with rock dumped to protect turbine foundations, said Blair Bailey, general counsel for the Port of New Bedford, Mass. New Bedford is the top East Coast port for scallop landings, with Cape May and Barnegat Light, N.J., not far behind.

“No one has any idea what the impact of offshore wind with be on commercial fishing,” said Bailey, citing a joint report by the industry group Responsible Offshore Development Alliance, BOEM and NMFS issued in March.

Offshore wind advocates who see unreasonable fears among critics need to understand “the fishermen have a fear of uncertainty,” said Bailey.

“Cape May County is at the forefront of climate change,” said Dan Ginolfi, an environmental consultant for the county at New Jersey’s southern tip. But offshore wind projects threaten the region’s economy and environment, he said.

Cape May’s fishing fleet is at risk along with the tourism economy, with the prospect of visitors seeing “an industrial powerplant lining the horizon for decades,” said Ginolfi. Cape May County officials have said they may join other wind project opponents in court challenges to developers’ federal and state permits.

Commenters on both sides of wind power said they are mindful of wind developers’ ongoing financial challenges with costs and supply chain issues. New Jersey state legislators this week could consider a measure to allow Ocean Wind 1 developer Ørsted to benefit from additional federal tax credits to help keep its plan for 100 turbines south of Atlantic Shores viable.

“The reason we’re here is to prevent catastrophic climate change,” said Sean Mohen, executive director of Tri-County Sustainability, an environmental program for three southern New Jersey counties.

At the same time, Mohen added, “let’s keep our eyes open” for offshore wind companies seeking more money to make up for their mounting costs. “Let’s make sure we’re looking at both sides of the balance sheet.”

Commenters repeatedly questioned why developers and BOEM did not foresee local reaction to the visual impacts shown in the DEIS. During an answer session near the end of the meeting, BOEM workers offered some historical reasons.

One local activist group, Save LBI, explicitly calls for moving wind turbines “35 miles out” away from sight of Long Beach Island residents.

The pathway toward today’s New Jersey wind leases was set in 2009-2010 New Jersey state meetings on future offshore wind, according to BOEM. Advisors then looked at what seafloor depths and distance from shore seemed feasible at the time, while being constrained by the large shipping lanes off New Jersey. Department of Defense advice played a role at the time too; airspace farther offshore is used for training Air Force and Navy pilots.

In the present planning, the first wind turbines could be glimpsed 8.7 miles offshore. In contrast, New York State energy planners, stung by early opposition to wind power proposals off Long Island, took the position that no new wind energy areas should be mapped less than 18 miles off the beaches.