Europe is heading into a predicted power crunch earlier than expected despite recent moves to curb demand and increase supply. The turmoil – due in large part to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and subsequent sanctions – could cause vast demand destruction across industries and consumers.

European governments and the power sector have lined up support packages to soften the financial blow but may need to consider some drastic moves before winter begins to bite, Rystad Energy research shows.

The hope that summer would bring a reprieve has not materialized, as gas flows drop and liquefied natural gas (LNG) cargoes reach their capacity limit. With temperatures rising, supply may not be sufficient to meet demand in addition to restocking ahead of next winter. Rystad Energy has reviewed Europe’s options to fill the power gap until longer-term solutions are in place.

In April, we expected the next European winter to be a tough time for consumers and governments. Our updated scenarios show that Europe will probably be heading into the storm much earlier than previously thought – and that the region will be underprepared for the chaos it will bring.

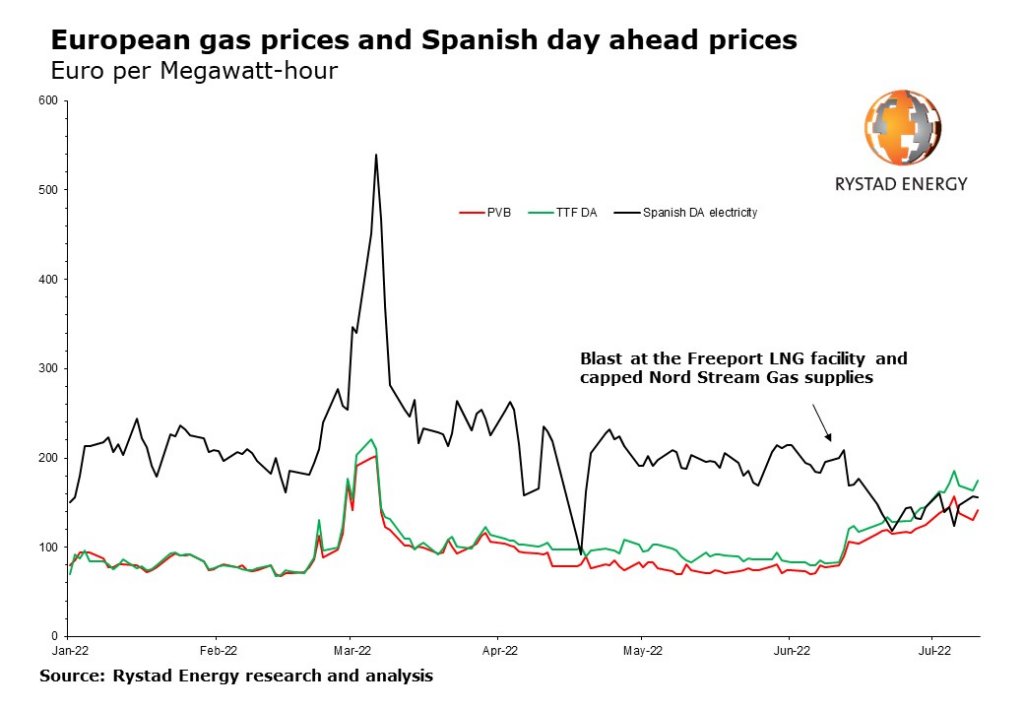

The uncertainty surrounding gas supplies to Europe is having a direct impact on power prices. Highly volatile gas supply has seen European power pricing swing far more wildly than before the war in Ukraine. At the start of Russia’s invasion in late February, prices spiked to a historical high of €530 per megawatt-hour (MWh) before stabilizing closer to €180 per MWh. Recent uncertainty surrounding Russian gas exports to Europe caused the baseload price to rebound to the current €278 per MWh – more than triple the price of a year ago. The surge in spot prices has lifted the forward curve, as the main uncertainty is for the winter when the supply/demand balance could get very tight.

“Europe’s options with regards to gas, coal, nuclear and renewables filling the power gap are extremely limited and costly. European governments have announced a raft of policies to secure more supply, support consumers and potentially curb demand should the crisis continue. The point at which the crisis will bite more deeply is looking closer and closer as we head into the summer and then autumn, this is increasingly a matter of ‘when’ and not ‘if’ the crisis arrives,” said Vladimir Petrov, senior power analyst at Rystad Energy.

Gas, LNG and reopening the Groningen field

In recent weeks, a double whammy hit European gas markets. First, it was confirmed that the Freeport LNG Development LP facility in Texas will be offline for 90 days before gradually ramping up production by the end of the year. Freeport LNG has over the past months exported most of its volumes to Europe – so with this development, 2.5% of Europe’s gas supply disappeared overnight. An even bigger blow was when the operator of the Nord Stream 1 pipeline from Russia to Germany said it would reduce exports from 167 million cubic meters per day (MMcmd) to just 67 MMcmd (Figure 2), instantly removing another 7.5% of Europe’s gas supply. This sent TTF gas prices surging from €83 per MWh on 13 June to €120 on 14 June and has since increased as Nord Stream 1 goes into a planned 10-day maintenance schedule.

Viable alternatives to Russian gas are limited in the short term. LNG terminals are running at full capacity, Norway is exporting as much as it can, and there is limited upside to exports from Azerbaijan and Algeria. If anything, the only major change on the supply side would be if the Netherlands were to ramp up supply from the veteran Groningen field. Groningen was once Europe’s largest gas field, with production of 55 billion cubic meters per annum (Bcma) – equivalent in supply terms to a full Nord Stream 1. The onshore field generated an increasing number of earthquakes over the past 30 years, and production has therefore been gradually phased out. The field has capacity to ramp back up to 20 Bcma relatively quickly if local and national governments permit, potentially offsetting a large share of the current shortfall from Russia. Such a restart at Groningen is speculative and could be politically contentious in the Netherlands, but it could clearly resolve many of Europe’s current concerns. So far, the Dutch government has only activated a plan allowing Groningen to produce 2.8 Bcm from the gas year ending in October 2023.