Recently, in Portland, Maine, professionals and companies from the offshore wind industry discussed floating wind technology at the Afloat Technical Summit.

Dr. Habib Dagher of the University of Maine discussed Maine’s procurement bill signed into law three months ago, calling for 3 GW of deepwater offshore wind power generation by 2040. The procurement bill is the first of its kind focused solely on floating offshore wind.

Walt Musial, offshore wind manager at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), noted that 80% of the global wind resources are in over 60 meters of water, requiring floating wind technology to harness it.

“Depth is really the main divider of how we use this technology. Around 60 meters is where we start to say, ‘Maybe that’s where the economic breakpoint is between floating and substructures’,” said Musial. “Floating substructures are different, they’ll be assembled differently, they’ll be deployed differently.”

Though futuristic thinking is certainly necessary in a new industry, there was a lack of discussion around the serious challenges that offshore wind is currently facing domestically. Last month, Avangrid, a Connecticut-based company owned by Spain’s Iberdrola Group, confirmed that it has reached its second agreement with regulators to terminate its previously approved Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) for the wind farms it is planning for in New England.

Avangrid has agreed to pay $48 million in penalties to Massachusetts for the termination of the PPAs. Also last month, the Massachusetts DPU agreed to the second walkaway this time for the SouthCoast Wind Project (formerly Mayflower Wind), which was to be developed through a joint venture between Shell New Energies and Ocean Winds North America.

A clear distinction exists between floating platforms and fixed substructures, yet many hurdles encountered in fixed-bottom offshore wind platforms will carry over to floating wind technologies. It's crucial to recognize that significant groundwork remains to be laid, as discussions and panels at times delved into advanced stages while fundamental issues persisted. At times, it felt panelists were discussing Step Five when the industry has not yet accomplished Step One.

Overall, the conference stimulated meaningful discussions on the holistic integration of floating wind technology. The key takeaways from two days of industry dialogue and expert insights were as follows:

• There is a need for commercialization.

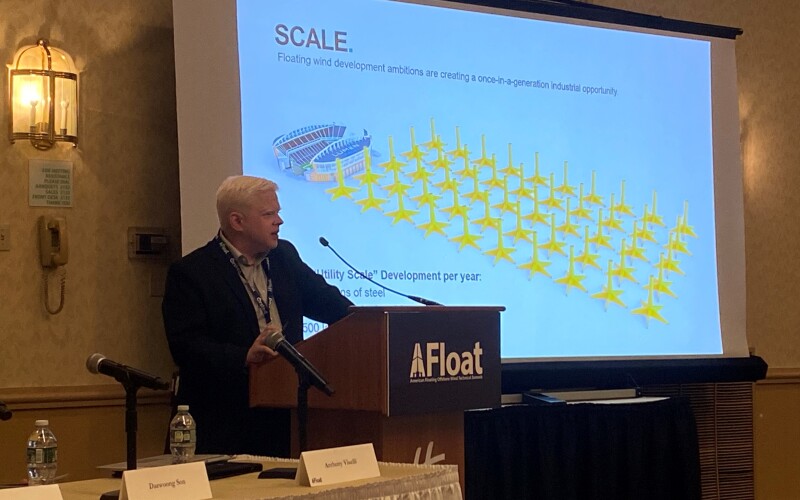

The Global Wind Energy Council forecasts 16.5 GW of floating wind will be generated by 2030. To put that in perspective, a nuclear powerplant generates about 1 GW. So, by 2030, the U.S. is expecting floating offshore wind to generate the equivalent of 16 nuclear powerplants. If producers are using the current standard floating wind 20 MW turbine, which panelists stated was a generous prediction, that equates to roughly 825 turbines on the water. When considering sheer weight alone, each of those floating wind turbines weighs roughly 15,000-17,000 tons.

“If we’re going to reach that goal, we can’t be waiting months for each (turbine), but we do need to get to the point where it’s only taking weeks,” said Chris Dorman of BW Ideol.

He claims that in Scotland, they’re capable of serially producing these floating wind platforms, and that it can be done locally by getting in with local supply chains. An example he provided were the use of concrete producers for their patented Damping Pool concrete floating technology.

DNV has put out an estimate that by 2050, floating wind technology will account for 264 GW of energy production. This would equate to 15% of all renewable energy, also noting by that year over two-thirds of all electricity will be generated from renewable resources.

In a whitepaper published two weeks ago, the Business Network for Offshore Wind contends that the U.S must invest $36 billion over the next decade to address the country’s offshore wind port infrastructure gap. These funds would flow to a minimum of 110 port sites across the East Coast, West Coast and the Gulf of Mexico to support the full buildout of the offshore wind industry.

“Our entire industry is challenged by scale, and that scale starts with the platforms themselves. We haven’t produced steel at this level for generations here,” Ben Ackren, CEO of Pelostar also spoke to the need for scale. “To achieve this target, we need to fabricate about 200,000 tons of steel per year. For the Gulf of Maine, we would also need about 40 kilometers of tendon cable to supply 50 turbines, and about 2,500 steel components that we can manufacture here in Maine.”

• Floating wind technology has been proven at shallower depths.

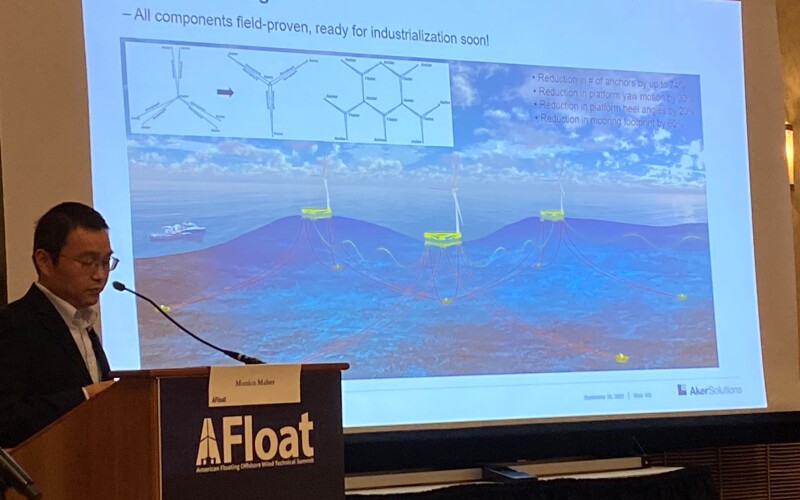

Design and technology aren’t the problem. Numerous companies revealed that their technologies work on smaller scales, and that they are innovating to be able to establish floating wind platforms at depths of 1,000 meters. Ben Ackers mentioned Pelostar’s tension leg platform (TLP), distinguishing it from barge platforms or semisubmersible platforms. Ackers spoke to the benefits of a TLP system.

“Rather than being connected to the seabed with taught or catenary mooring systems that are spread over the seabed, our mooring tethers are purely vertical. We call those tendons,” Ackers said. “In addition to having a dramatically smaller footprint on the seabed, TLPs tend to have hulls with lower mass, which reduces capital expenditures to build these platforms, and they also have about 10 times less motion. The obvious benefit of that, is that you provide a better environment for the turbine to reduce wear and tear on that turbine, and also to maximize annual energy production, which increases revenue for the developer."

“We have solid solutions here in the Gulf of Maine, which has water depths in the range of 100-to-200 meters,” Ackers continued. “Achieving the economics that we’re targeting for offshore West Coast is more of a challenge, because you have to buy more tendon material. So, our team is very focused right now on innovating solutions to address this challenge, by looking at different tendon materials, different platform configurations, and innovative installation methods to meet the challenge of deploying these in ultradeep water.”

• The lack of Jones Act-compliant vessels will be a big problem.

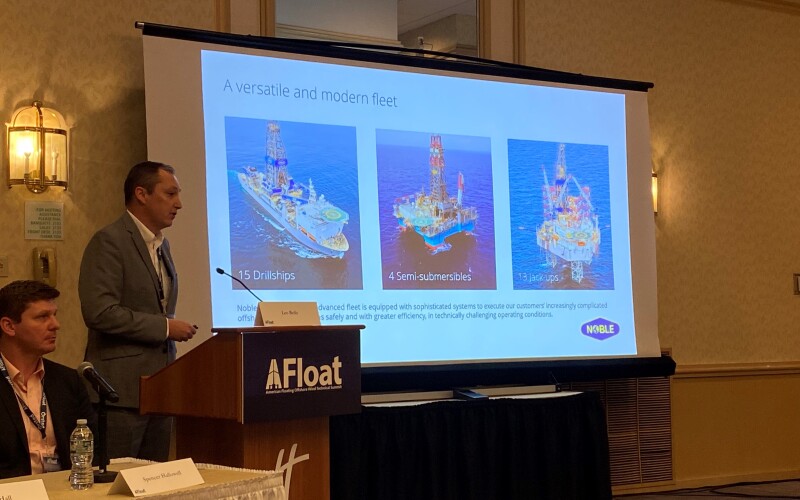

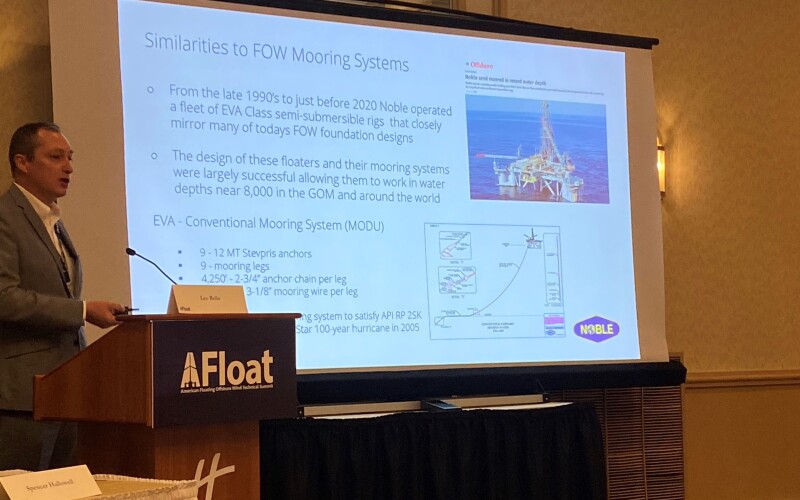

Of the panels attended, only one panelist mentioned the urgent need for vessels that can install these technologies. Jeremy Abercrombie, marine operations manager, Noble Drilling Services Inc. brought up how the technology from the oil and gas industry can be applied to help reach the mooring depths of floating wind and their anchor systems. The U.S.-based drilling company is a vessel owner and operator that owns a fleet of 32 vessels.

Abercrombie posed a question to the crowd, “Where are the vessels that we’re going to need? Are those vessels in the conversation? You have an idea for a foundation or a mooring component that’s going to be in there, but how do you install it?”

Abercrombie spoke to the overlap between the oil and gas industry and the foundations for floating offshore wind technology. “The oil and gas industry is what we do on a daily basis. We’ve moored our rigs for years, while there are differences, there are similarities; the fact that we have to meet design codes, design standards, insurance, warranty, all of those things. There’s been a lot of talk about supply chain and about lowering the cost of all of these components; well, vessel costs, and vessel mobilization and all those things, not really a key component right now, but is one of the biggest challenges from what I understand. In Europe, the spot market is way different than the spot market in the U.S. So, the amount of vessels that are available to you, and the combinations that you use to install these components. I do think it’s something that we really need to talk about. We need to look at the vessels that are available to us and is that really a part of your supply chain component? Because when you submit a tender, the vessel mobilization and the vessel cost is just as much as the TNI scope. It’s more. Because we’ve done it.”

BW Ideol’s Chris Dorman aptly summarized the conference's essence, emphasizing the need for bankable solutions and prudent decision-making in these early stages. “That’s what the people who already have floaters in the water offer to the early stage. Banks have been able to see the technology to start getting comfortable with it. So, that it’s not a brand-new thing that we’re trying to make one hundred of,” said Dorman, emphasizing the need to be cautious in the early stages of this industry.

“Onshore has had this great story to tell of cheaper every single year,” Dorman continued. “We can just watch this cost curve go down, and the reason it’s gone down is because we’ve industrialized that process. We need to make sure people are fully onboard with the costs required to build out the port. This is expensive, so this first project is not going to be this bargain basement cheap price. These are going to be very expensive projects for the first one.”

The summit received strong congressional support, with attendees including both Maine senators — Susan Collins, and Angus King, as well as the state’s governor, Janet Mills.