While at home in Massachusetts a few days ago, digging through old boxes and packing new ones to help my elderly father downsize into a smaller apartment, I came across my mother’s old travel diary from a cruise taken in the summer of 1951.

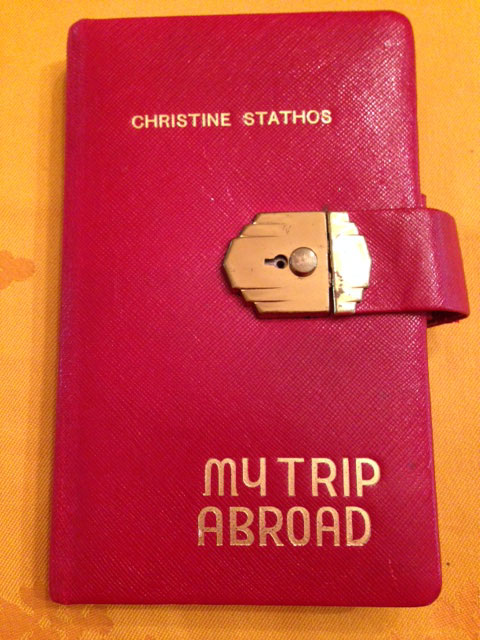

It was a beautiful red diary made by a stationary company in Massachusetts, complete with her name and “My Trip Abroad” engraved in gold letters and secured with a lock (key long gone). I was fascinated by her daily entries of shipboard life on the crossing between New York and Southhampton, and her impressions of London, Cherbourg, Paris, Venice, Lucerne and Athens, just six years after the end of World War II.

Cruising back then was a big deal. She received flowers upon her departure from friends and relatives, had three lavish farewell parties and received numerous telegrams wishing her a bon voyage. As gifts, she was given “two nylon blouses, eight rolls of film, six pairs of stockings, Chanel cologne, a leather passport holder and soap (which the diary notes is “rarely furnished in foreign hotels”).

But what I found even more interesting and intriguing was the text at the beginning of the diary that was written to prepare the cruise traveler for the journey. This gave a unique window onto steamship travel, as it was called in those days, and the privilege and luxury of it all compared to the mass production cruise ship experience of today.

“In planning a trip abroad remember that only half the pleasure is in the actual trip,” the introduction says. “A small portion is in the anticipation, and a large portion in the memories. If you keep a careful record of your pleasant days afloat and ashore, and especially if you supplement that record with freely purchased postcards or patiently taken photographs, you can have the most delightful of after — pleasures -living your trip over again.” Postcards? Who buys those anymore in a day of instant messaging and Instagram?

It advises about the timely filing for a passport ($10), about carrying funds on the ship (traveler’s checks or letters of credit will do) and advises to arrive early for the sailing so that a dock porter can carry baggage aboard and place it in the stateroom (a tip of “10-25 cents per piece of baggage will be sufficient.” ) It also advises to rent a deck chair as soon as possible (ask for one on the “sunny side — the starboard going east, and the left (port) going west when north of the equator”) and suggests to find the bath steward to arrange the hour of her bath. (!)

Once underway, she will locate her deck chair with her name written on a card in a holder on the back, and the deck steward will take care of her every need and “assist to wrap you up comfortably.” He will also serve hot bouillon at 11 a.m. and tea every afternoon at five.

Now onto the on-ship amusements. Forget the waterslides and golf practice. The Queen Elizabeth offers deck tennis, shuffleboard, tether ball and bean bag competitions. The deck steward will recite the rules. There’s also horse racing with miniature horses “whose progress is governed by the roll of dice” and there are lots of betting games, including the Auction Pool, based on the total number of nautical miles covered by the ship in a day.

Meals are a big deal and are announced by bugle or gong. Expect a “fancy dress ball” and a Captain’s dinner and dancing just about every night. And of course, it is customary on European crossings to put your shoes outside the cabin door at night to be cleaned.

Passengers are advised not to bother the ship’s crew, “as they are fully occupied with running the ship.” But those who are “fortunate enough to make the acquaintance of the ship’s officers are sometimes invited, in fair weather, to visit the bridge, the engine room or other parts of the ship ordinarily not open to passengers.” But for the most part, “it is best to refrain from bothering the ship’s officers, especially with frequent questions.”

It explains that the ship is navigated by a gyroscopic compass. The ship’s position on the sea is checked each day at sunrise, noon and sunset by observing the altitude and bearing of the sun, through a sextant. “By comparing these figures with the time as shown by the chronometer and with tables of figures for the particular day of the year, the officers can determine with remarkable accuracy the exact position of the ship on the ocean.”

“The skillful navigator brings his ship across 3,000 miles or more of water and arrives unerringly at his destination with as little difficulty as you drive from the country club to your own garage.” Now that’s an interesting comment on the skill of the crew, and on the cruise industry’s customer base in the 1950s!

Aids to navigation included radio direction finders, submarine signals for communication with shore, instantaneous sounding devices and sensitive instruments to measure the water temperature so that “the presence of an iceberg can be detected 15 miles away.” Thank the Titanic for that one.

There are lots of tips about visiting European countries after landing.

“Drinking water is by no means as safe abroad as at home,” you should “shop for a hotel room like the natives” by asking to see rooms first and negotiate the price, and it is suggested that the traveler “learn about the manners of the country before plunging into the local culture. In France, it notes that “a gentleman raises his hat whenever he meets anyone or to the public in general when entering or leaving a store or railway carriage or a restaurant, and he asks permission, with at least a bow, before sitting down at a restaurant table where there are others.”

Ah, those were the days!