Forecasters’ early computer modeling showed Hurricane Joaquin would likely head north-northwest, away from the Bahamas, before falling apart under high altitude shear winds – except for one outlier result that showed the first indication of a movement toward the southwest.

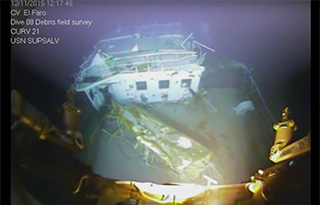

That was where Joaquin went Oct. 1, 2015, sinking TOTE Services 790’ ro/ro containership El Faro, killing her crew of 33 and smashing the nearby islands. A Coast Guard marine board of inquiry is looking at the weather information Capt. Michael Davidson and his crew had in the hours before the sinking.

“The physical problem we were dealing with in Joaquin was (wind) shear that was not too strong and not too weak, but something in the middle,” said James Franklin, branch chief of the hurricane specialist unit at the National Hurricane Center in Miami, as he explained Tuesday the workings and shortcomings of hurricane modeling to the Coast Guard panel meeting in Jacksonville, Fla.

In testimony Monday, board members heard how Davidson had planned his course from Jacksonville to San Juan, Puerto Rico, to pass west and south of Joaquin’s forecasted path. But the storm took its swing toward the El Faro’s path as the vessel suffered a major casualty to its main propulsion.

The consensus forecasted track for Joaquin three days before Oct. 1 was off by 562 miles, an unusually large error by modern forecasting standards, and was still off by 180 miles in the 48-hour forecast. The Coast Guard board is looking at both the accuracy of those forecasts, and their timeliness in getting to the El Faro. The El Faro was subscribed to the Bon Voyage weather tracking system operated by Applied Weather Technology (AWT), Sunnyvale, Calif.

Those forecasted storm tracks were four to five hours old when delivered to ships as part of tropical data files, updated every six hours, AWT’s Jerry Hale testified Wednesday.

“We’ll update each ship to make sure it is safe,” said Hale, whose company charges around $300 to $1,200 for the service, depending on the customers’ voyage length and time.

Board members focused in detail on the time elapsed between storm data reported by the National Hurricane Center – which needs about three hours from the time of data collection – to when full updates were put out by AWT on a six-hour schedule and could be seen by the El Faro’s crew.

“You’re putting out data that’s nine hours old?” said William Bennett, a lawyer representing Davidson’s widow Theresa.

Under questioning, Hale and AWT colleague Rich Brown described options offered on their company’s system that allow subscribers to get additional information such as wind and wave data more frequently. But none had been requested for the El Faro, they said.

Armed with super computers, hurricane modelers have made remarkable strides in predicting the likely paths of storms, but lots of uncertainty still exists in forecasting, Franklin said.

“We can only estimate wind speed within about 10%. When it is (predicted) 100 knots, it could easily be 110 knots, it could be 90,” he said. Estimates of storm size can be off by 25%, and despite advances in the last three to four years, meteorologists can still be surprised by sudden increases in storm intensity, he said.

As a tropical storm, Joaquin began to quickly intensify Sept. 29, and became a hurricane in the early morning hours of Sept. 30 when it was 170 nautical miles north-northeast of San Salvador in the Bahamas, according to a National Hurricane Center synopsis.

That evening, it was upgraded to a major hurricane and the center had moved to within 90 miles of the island, moving in on the El Faro as the crew tried to repair the steam propulsion plant.

“Joaquin is a real good example of how far we have to go,” Franklin said.