As promised, the Biden administration is speeding environmental reviews of East Coast offshore wind projects.

That’s raising alarms among competing interests of the fishing and coastal tourism industries. But even with the worldwide movement toward offshore wind power, its emerging limitations may allow more time for compromises.

Globally, $810 billion could be spent developing offshore wind power by 2030, analysts at Norway-based Rystad Energy predict.

Despite broad federal government support – the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management is looking to have environmental studies underway for as many as 10 projects this year – the U.S. market may see only $70 billion of that investment during the 2020s, Rystad reported.

With offshore wind turbines’ physical size and developers’ ambitions getting bigger, the global demand for large wind turbine installation vessels will make it very expensive to hire foreign-flag WTIVs to cross the Atlantic.

The first U.S.-flag WTIV is under construction for Virginia-based Dominion Energy, whose planners see it not just as a requirement for building their own 2.6-gigawatt offshore project but a long-term merchant vessel enterprise to serve other developers.

With about three years and $500 million required to build WTIVs, that gap – and the broader Jones Act legal and regulatory requirements to employ U.S. vessels and mariners – will constrain wind project construction here, Rystad predicts.

BOEM is plunging ahead. A month after starting the review process for Ørsted’s Ocean Wind project off New Jersey, the agency announced April 29 it was starting the environmental impact statement process for Revolution Wind, an 880-megawatt project south of Massachusetts and Rhode Island.

Mayflower Wind LLC, another would-be neighbor in the southern New England offshore wind power development area, has scheduled a May 18 virtual online public information session to pitch its plan for the waters south of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket – perhaps a prelude to its own EIS debut.

Nantucket Sound, between the island and the south shore of Cape Cod, was proposed for Cape Wind, an early offshore wind venture that succumbed to legal challenges from wealthy seaside homeowners and others. BOEM, state energy planners and wind developers took that lesson in moving future renewable energy enterprises farther offshore.

Nevertheless, the prospect of seeing wind turbines arise on the far horizon is again raising alarms in prosperous resort towns.

Off New Jersey, Ocean Wind, a 75/25 percent joint venture of Ørsted and the PSEG utility group, could be sending power ashore in 2024. The 1,100-megawatt array would be built between 15 and 27 miles offshore on Ørsted’s federal lease east of Atlantic City, with up to 98 turbines feeding power to three offshore substations.

Ocean Wind turbines array would be laid out on a grid of 1 by 0.8 nautical mile separation between the turbine towers, an arrangement Ørsted planners say will allow passage for fishing vessels from the ports of Barnegat Light, Atlantic City and Cape May.

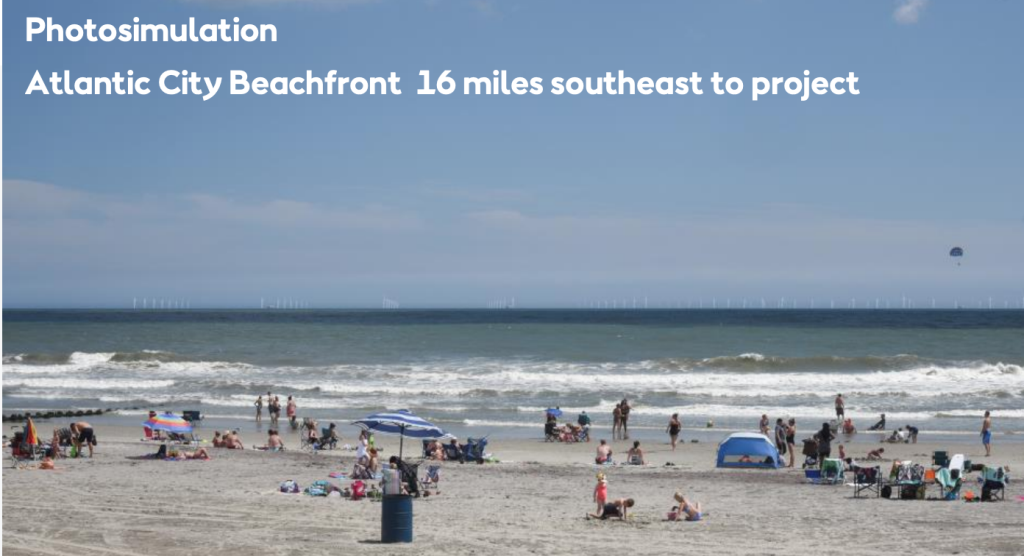

Ørsted also changed its turbine layout design in response to concerns from beachfront communities about the visual impact of turbines, according to Pilar Patterson, Ørsted’s project manager for Ocean Wind. Video simulations produced by the company portray turbines closest to shore at 15 miles as blades and nacelles just visible above the horizon, when there is not a layer of marine haze obscuring them.

Those outreach efforts by developers of Ocean Wind, and the neighboring Atlantic Shores partnership between Shell New Energies US LLC and EDF Renewables North America, have not mollified commercial fishermen and homeowners on New Jersey’s Long Beach Island.

Climate change and sea level rise are serious threats to the barrier island. But offshore wind skeptics worry what changes that industry may bring, and town governments on the island have expressed formal opposition.

“We’re very concerned about the impact on tourism,” said Beach Haven, N.J., Mayor Colleen Lambert during the April 15 meeting on Ocean Wind.

The Ocean Wind tract at its closest is 15 miles offshore and turbine blades could be visible from shore on some days, according to BOEM visual simulations.

Lambert noted New York has set an 18-mile minimum in its policy to prevent visual objections.

“It would be nice if the process slowed down,” she added.

The Rystad Energy report suggests market and regulatory forces may grant the mayor’s wish.

“Europe, as the most mature market, is still expected to dominate offshore wind spending this decade, totaling about $300 billion,” according to Rystad. “China dominated annual spending between 2019 and 2021 due to its substantial annual capacity additions. This decade, the country is forecast to spend about $110 billion.

“Meanwhile, the Americas region is falling behind due to the U.S Jones Act and delayed permitting processes for the US offshore wind industry, which are pushing back the expected start-up years for a number of wind farms. The region is expected to spend just over $70 billion this decade on offshore wind projects – still a significant sum, but well below that of other global regions.”