The maritime industry, more than either land or air transportation, is abuzz with anticipation of autonomous vessels.

With the major class societies furiously adjusting their standards to account for automated decision-making in voyage-planning and vessel operation, and with several test prototypes now navigating Northern European waters, the future of computer-guided navigation is here.

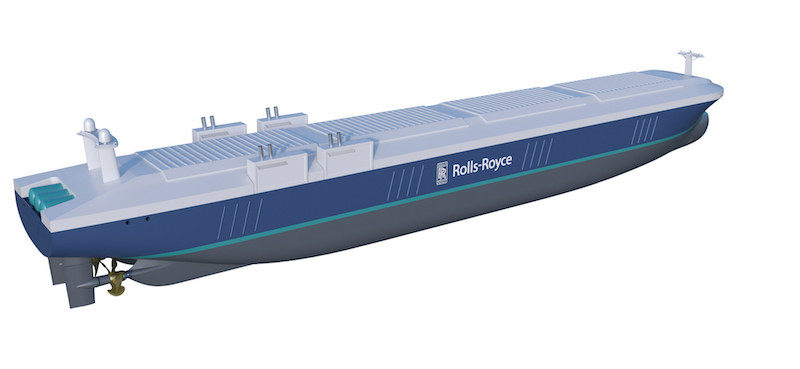

At next summer’s Autonomous Ship Technology Symposium 2019 in Amsterdam, expect to see even more innovation introduced. But by then, Rolls-Royce may have deployed the first fully autonomous vessel from its state-of-the-art research facility for autonomous ships in Turku, Finland. The $10 million project opened last January, according to a white paper prepared by Rolls-Royce, to “bring together ship designers, equipment makers, and universities to examine the future of autonomous ships.” Rolls-Royce intends to deploy autonomous vessels on short runs within the next two years, with commercial long-range deployment by 2025.

“The technologies needed to make remote and autonomous ships a reality exist,” according to the white paper. “The necessary sensors, the communication equipment, the programming, etc. (are) all currently achievable.”

The good news for mariners is that there are no current plans for unmanned autonomous vessels. This would require a sea change in international navigation rules, which mandate watchkeeping on all vessels under navigation. With modern electronic integration of radar, depth sounding, position-finding and steering systems, watchkeeping on modern vessels is already more of a monitoring job than real-time manipulation of controls. However, COLREGS (International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea) and the navigation rules of all countries, at least for now, require humans onboard to monitor the vessel’s radar and other navigation systems, and to maintain visual watch for traffic and other obstacles.

It’s difficult to imagine how that could change. Even with today’s technological advances, propulsion itself depends and will continue to depend in the near future on the 140-year-old diesel engine. And although fully automated maintenance and at-sea repair of diesel engines may be possible someday, that’s a long way off. Also, the massive effort that an overhaul of COLREGS would require — to account for unmanned vessels integrating with manned vessels and responding to challenges presented by the ever-changing sea — suggests that the easiest and most-practical course is to plan for manned autonomous navigation.

Certainly, there’ll be a reduction in manning requirements, continuing a trend that started 200 years ago with the transition from sail- to engine-power, and there’ll be a shift from the traditional seafaring skills of “hand, reef, and steer” to computer-related skills, but for those who want to go down to the sea in ships, the jobs will still be there.