The buzzword at the Federal Aviation Administration regarding aerial drones (unmanned aircraft) is “integration.

In U.S. airspace, drones will never be commercially useful until they can fly safely when admixed with manned aircraft, which is why the FAA has already begun its Unmanned Aircraft System (UAS) Integration Pilot Program (IPP). The fact that the FAA is willing to consider this possibility is momentous, and now Uber, Google’s Larry Page, and top execs from Airbus and Audi are strapping themselves into the VTOL (vertical takeoff-and-landing) drone movement. There are prototypes now flying and the electronics are here already, so integration of pilotless aircraft into the national air-traffic system is coming, and faster than anyone could have imagined 10 years ago.

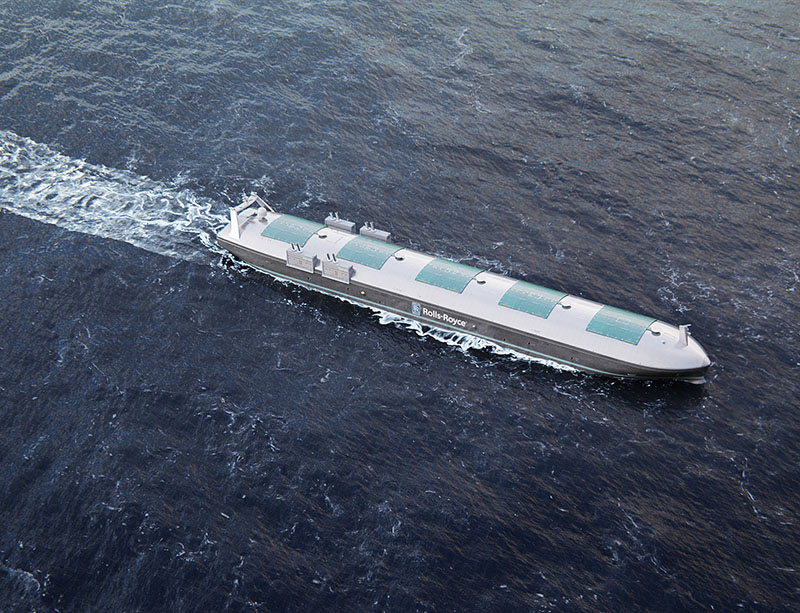

Fortunately for the companies like Rolls-Royce that are moving at full-sea-speed toward unmanned waterborne vessels, the challenges of integration of manned and unmanned vessels are both simpler and more complex. Speeds are much lower and vessels essentially operate in two dimensions rather than three. But there are many more vessels that cannot being effectively monitored, and there will always be a collision hazard between them and vessels under autonomous operation. Legally, the operators of autonomous vessels, even remote operators, will be held to the same laws, regulations, and standards as crewmembers on manned vessels. But whether a jury will convict a computer programmer in Norway of manslaughter for a computer glitch causing a fatal accident on the Lower Mississippi River — and whether such a verdict can be enforced — remains to be seen. For the crewperson onboard, however, the legal risks remain the same, just as the airline pilot is still ultimately responsible for his or her plane.

Interestingly, aerial drones in the U.S. will operate with considerable freedom compared to unmanned vessels. The FAA has virtually complete control over U.S. airspace and can mandate their integration into the national air-traffic system. The U.S. Coast Guard, however, which has primary control over the nation’s waterways, is constrained by COLREGS, the international convention for the prevention of collisions, which makes no exception to its manning requirements. There doesn’t seem to be any movement toward amending COLREGS, so autonomous but manned vessels are the only foreseeable possibility, even though the ability of a trained crewperson on an autonomous vessel to take over at 20 knots and avoid a collision, and of a tired businessman to take over and successfully land a malfunctioning aerial drone, are entirely levels of skill. In any event, it appears that once again the marine industry will be following the aerospace industry in adapting to new technology.

So what will the mariner onboard an autonomous vessel look like and what will they do? What will be their legal liabilities? First, the mariner will be a computer technician rather than a shiphandler. Just as computers land today’s airliners and the pilots are there to make sure the computers get it right, the mariner's job will be to enter the necessary commands into the vessel’s computers to execute the operator’s intentions, including any emergency collision or allision avoidance. The mariner must also have the computer skills to facilitate shore control of the vessel’s machinery. This is already a reality on vessels powered by the latest generation of Caterpillar engines, which can be monitored in real time during navigation — and actually controlled to some degree — by shore technicians.

Just as the present trend is away from onboard repair and toward engines that require shore support for even minor repairs, the “black gang” on an unmanned vessel won’t be casting bearings or rebuilding turbos. Instead mariners will be monitoring computer screens and coordinating by email with various management and support personnel for required maintenance and repair.

If the prospect of going to sea in an air conditioned cubicle with little reason to leave its comfy confines, or of finding the engine room a strange and barren space on that rare occasion when a visit is necessary, is less appealing than the world of “hand, reef, and steer” and grease gun and spanner, then we must remember that there were many seafarers who never adjusted to the transition from sail to steam. It’s still going to sea, after all, and we can only hope that even unmanned vessels will have a place where a crewperson on a long watch can take the sea air and scan the wide horizon. Even with a computerized Iron Mike at the helm, there’s nothing like a sunrise at sea.