This might not be a workboat story, but who doesn't love a good fish story?

Last Halloween, Chesapeake Beach, Md., charter boat captain, Shawn Gibson, made the most exciting catch of his life — in his parents' backyard — a quarter of a mile from the Chesapeake Bay. The fisherman and his family made a major paleontological find when they unearthed the fossilized remains of a 15-million-year-old snaggletooth shark while digging footers for a deck.

The Gibson family home is also located in one of the richest deposits of Miocene fossils in the U.S., if not the world. So the Gibsons are familiar with what sharks' teeth and bones. When Shawn's brother, Donald, was digging footers for the porch, he noticed a large number of shark vertebrae in the dirt.

The thing about living in the middle of an epic fossil deposit is that there are plenty of people who get interested and educated on the subject. So there is usually someone to call if you find something interesting. Shawn called his mate, Scott Verdin, on Wound Tight, his charter fishing boat. Verdin is an amateur fossil hunter. He immediately recognized the significance of finding so many vertebrae together.

"We dug carefully every day after work. We had cleared about 18 inches of dirt, and I found three vertebrae in a row and then a tooth that was an inch and a half, that was really cool," Gibson said. He remembers that a friend immediately identified the tooth as being from a Hemiprisits serra, an extinct snaggletooth shark. It was clear that the Gibsons had discovered something rare, and it was time to call in the experts.

Shawn called the Calvert Marine Museum and spoke with the curator, Dr. Stephen Godfrey. Godfrey's assistant, John Nance, said that he could tell that his boss was "visibly excited," after the call. The two work closely together in the jam-packed paleontology lab at the museum in Solomon's Island. Nance shared Godfrey’s excitement, “This is not the kind of call you get everyday.”

The two arrived at the Gibson house on the afternoon of Halloween, a week after the first vertebra was discovered. Nance went around to the site first and he said he will never forget the feeling of seeing the semi-unearthed skeleton, "It was jaw-dropping,” he said. "I knew immediately I was seeing something that most paleontologists only dream of, especially those who study marine fauna." The shark appeared to be buried completely intact — a whole skeleton in one place. This is highly unusual, according to Nance, since in a marine environment dead animals would tend to be picked at by scavengers or broken up by the water. "It is just amazing to see a whole shark from 15 million years ago."

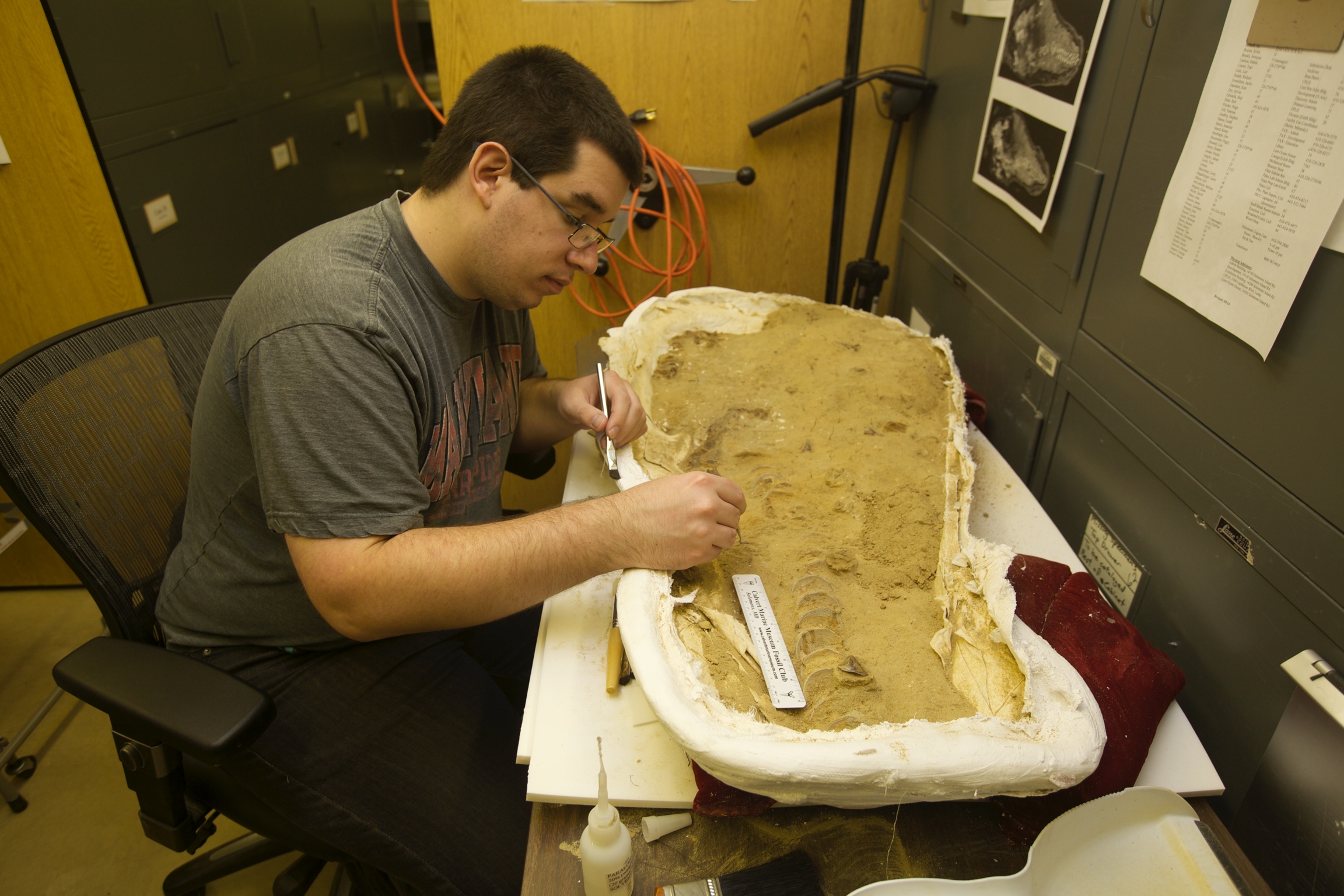

Godfrey and Nance carefully dug down around the skeleton and created a plaster of Paris cap over the find. When it set, they dug it out and flipped it over, the skeleton in was in a small open coffin. They now have the shark in the lab where Nance is painstaking removing the sand from around it with dental tools so it can go on display in the museum.

Meanwhile, Shawn Gibson, the fisherman, feels a bit guilty about making the discovery. “You know, it’s like a fishing tournament. We get all geared up and know exactly what we are doing and some guy who has hardly fished comes along and catches the winning fish,” he said. “Here we are, not big fossil experts and here we find the prize when we weren't even looking."