A loose wire in a circuit breaker on the containership Dali likely triggered electrical failures that sent the 984’ vessel careening into Baltimore’s Francis Scott Key Bridge in March 2024, the National Transportation Safety Board said Tuesday.

NTSB investigators believe the wire – attached to an electrical breaker block when the Dali was built a decade ago – was not properly seated in the block, leading to the first failure at 1:25 a.m. March 26.

The resulting allision sent the center 1,200’ span plunging into the Patapsco River, carrying six highway construction workers to their deaths, and closed the port of Baltimore for weeks.

“One wire, among thousands,” NTSB Chair Jennifer Homendy said near the conclusion of the board’s hearing in Washington, D.C.

Often the safety board comes under intense pressure to release definitive findings soon after a high-profile accident like the Key Bridge collapse, but history shows the agency’s investigative systems and detailed analyses yield definitive conclusions, said Homenday.

“Our findings in this case are a perfect example,” she said.

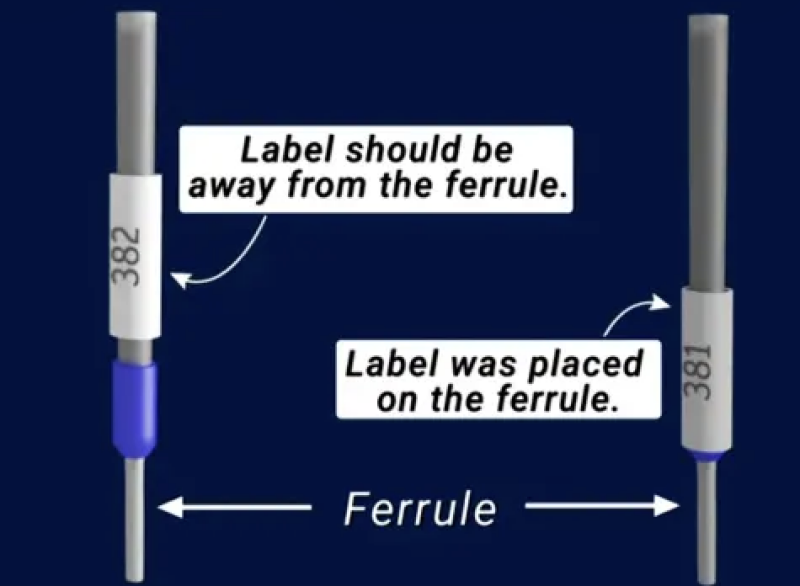

In combing over the Dali’s electrical systems with industry experts, investigators found that wire-label banding prevented the suspect wire from being fully inserted into a terminal block spring-clamp gate, causing an inadequate connection.

In a statement Homenday cited the sheer volume and complexity of the case.

“But like all of the accidents we investigate, this was preventable,’’ Homendy said. “Implementing NTSB recommendations in this investigation will prevent similar tragedies in the future.”

A major finding of the board is how two decades of escalating, post-Panamx containership traffic has crowded and constricted U.S. ports.

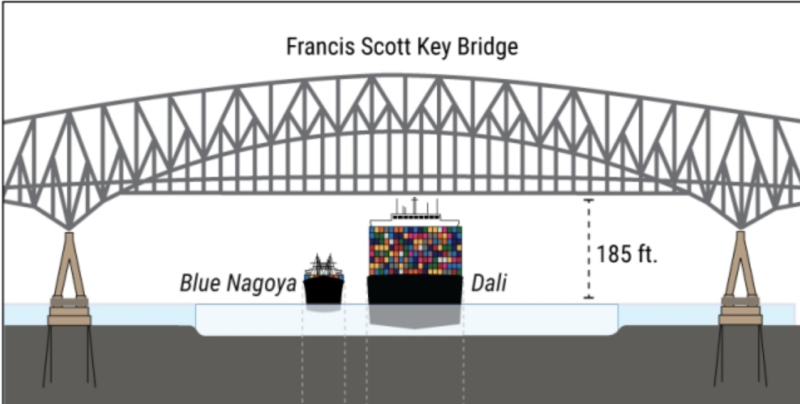

“Contributing to the collapse of the Key Bridge and the loss of life was the lack of countermeasures to reduce the bridge’s vulnerability to collapse due to impact by ocean-going vessels, which have only grown larger since the Key Bridge’s opening in 1977,” the board noted in a summary late Tuesday. “When the Japan-flagged containership Blue Nagoya contacted the Key Bridge after losing propulsion in 1980, the 390-foot-long vessel caused only minor damage. The Dali, however, is 10 times the size of the Blue Nagoya.”

In March the NTSB released an initial report on the vulnerability of bridges nationwide to large vessel strikes. The agency Tuesday reiterated how that report “found that the Maryland Transportation Authority – and many other owners of bridges spanning navigable waterways used by ocean-going vessels – were likely unaware of the potential risk that a vessel collision could pose to their structures. This was despite longstanding guidance from the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials recommending that bridge owners perform these assessments.”

The NTSB sent letters to 30 bridge owners identified in the report, urging them to evaluate their bridges and, if needed, develop plans to reduce risks. All recipients have since responded, and the status of each recommendation is available on the NTSB’s website.

As a result of the investigation, the NTSB issued new safety recommendations to the U.S. Coast Guard; U.S. Federal Highway Administration; the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials; the Nippon Kaiji Kyokai (ClassNK); the American National Standards Institute; the American National Standards Institute Accredited Standards Committee on Safety in Construction and Demolitions Operations A10; HD Hyundai Heavy Industries; Synergy Marine Pte. Ltd; and WAGO Corporation, the electrical component manufacturer; and multiple bridge owners across the nation.