The National Transportation Safety Board is calling for improved updating and communication of hurricane risks to mariners, based on its investigation into how the ro/ro containership El Faro was sunk and 33 lives lost during hurricane Joaquin.

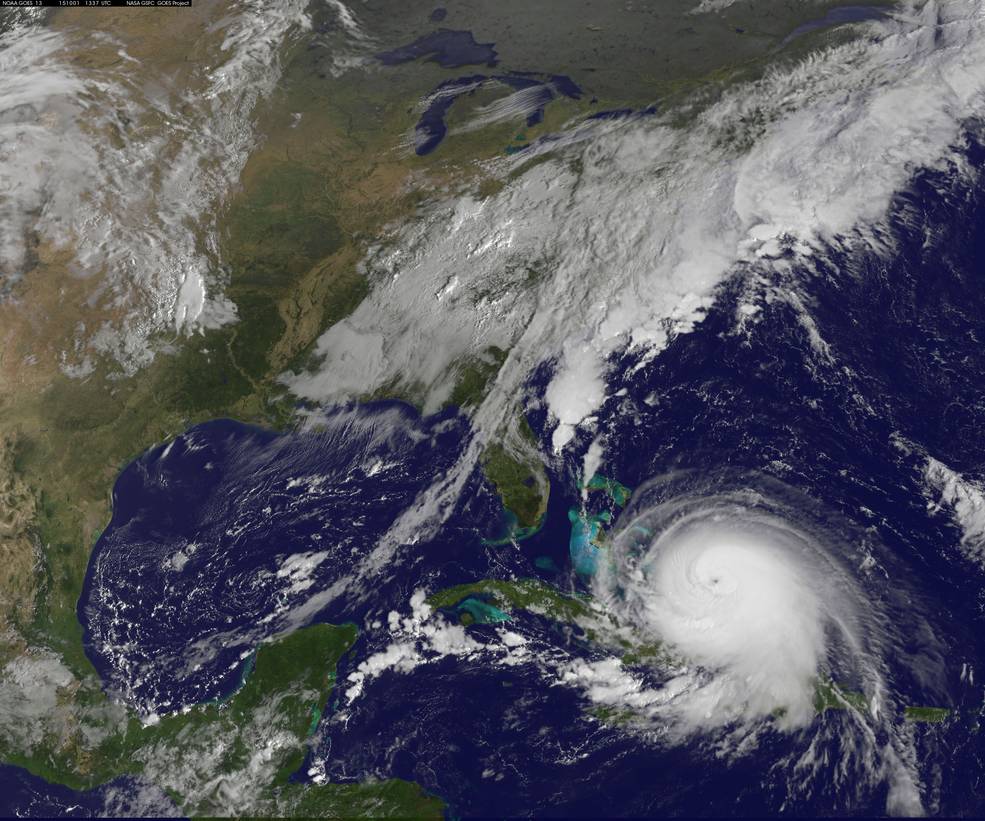

The NTSB has yet to conclude its investigation into the deadly Oct. 1, 2015 sinking, when the 790’ TOTE Maritime ship lost power close to the eye of the category 4 storm. But the agency says its findings so far — including analysis of crew conversations from the ship’s voyage data recorder and detailed review of National Weather Service updates during the storm — make a compelling case for improvements.

“The factual data revealed that critical tropical cyclone information issued by the NWS is not always available to mariners via well-established broadcast methods,” the NTSB report says. “The data also suggest that modifying the way the NWS develops certain tropical cyclone forecasts and advisories could help mariners at sea better understand and respond to tropical cyclones.

“Further, factual data on the official forecasts for Hurricane Joaquin and other recent tropical cyclones suggest that a new emphasis on improving hurricane forecasts is warranted.”

The El Faro was on its Jacksonville, Fla., to San Juan, Puerto Rico run when it transmitted distress alerts around 7:15 a.m. The ship was about 40 miles north of Crooked Island in the Bahamas, close to the hurricane eye.

During hearings in Jacksonville, a Coast Guard board of marine inquiry heard examined evidence and heard testimony about warnings and updates from the National Hurricane Center in Miami, and how El Faro captain Michael Davidson and his crew received them.

Among the big questions pursued by the Coast Guard and NTSB is why the El Faro got so close to the storm center, and why the captain and crew did not get more timely warnings about changes in the storm’s course.

The El Faro. TOTE Services photo.

Post-Joaquin reports and meteorologists with the National Hurricane Center told NTSB investigators how Joaquin was particularly difficult to predict. One assessment by their parent agency, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, recounted how “the GFS (Global Forecast System model) had a very difficult time capturing (Joaquin’s) initial track. This resulted in less warning given to the Bahamas, where significant storm impacts occurred.

“In conversation… NHC staff told NTSB staff that Joaquin was one of the most challenging storms for forecasting track.”

Computer models had particular trouble defining the cyclone’s vertical structure, and early on anticipated that wind shear would be too strong for significant development. That predicted that Joaquin would remain relatively weak and move to the west and northwest.

Instead, “Joaquin strengthened, became a deep system, and moved southwest,” the report notes.

One NHC official told the board of inquiry “the physical problem that we were dealing with in Joaquin was how was this particular tropical cyclone going to respond to shear that was not too strong and not too weak but somewhere in the middle . . . Joaquin’s a real good example of how far we still have to go.”

The report goes into detail about other aspects of hurricane modeling, forecast updates, and the channels for communicating those changing risks to mariners. The NTSB made recommendations for NOAA, the National Weather Service and Coast Guard, including:

• Develop a plan to improve tropical cyclone models to improve their performance in shear conditions.

• Get technology to help National Weather Service forecasters quickly sort through large numbers of tropical cyclone forecast model ensembles and identify most likely scenarios.

• Work with international partners toward a plan to ensure immediate dissemination to mariners, via Inmarsat-C SafetyNET and future technology of NWS Intermediate Public Advisories and Tropical Cyclone Updates.

• Ensure that advisories and updates are issued at three-hour updates between regular tropical forecasts via Inmarsat and future technologies, including coordinates of the current storm center position, maximum sustained surface winds, current movement, and minimum central pressure.

• Messages should include the time of next advisories so mariners can anticipate the next update.

• Provide advisory packages over other media channels including TELEX and FTP (file transfer protocol) e-mail service.

• Solicit feedback, comments and advice from the professional mariner community, especially ship masters.