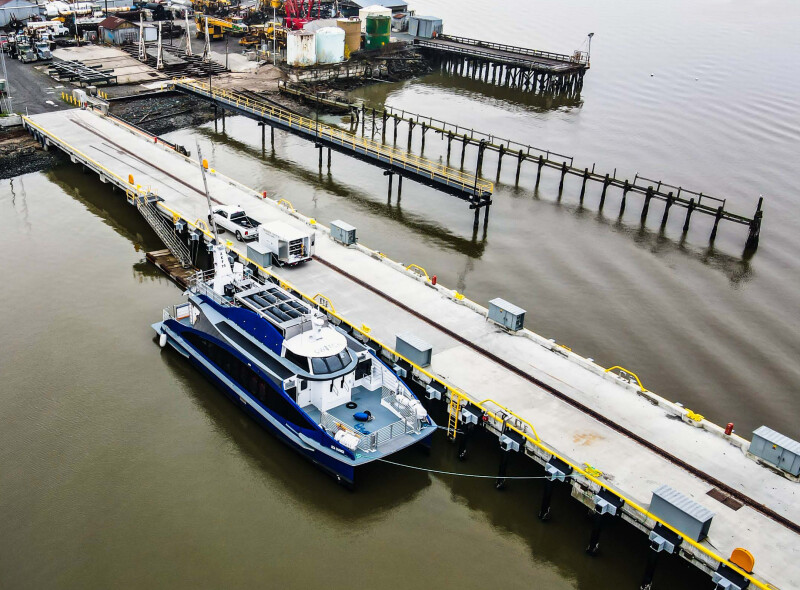

Last summer, San Francisco Bay Ferry put the first hydrogen-fueled vessel in the United States into commercial service. The 70' Sea Change carried passengers between tourist haunts along Fisherman’s Wharf and the Ferry Building in downtown San Francisco during a six-month trial.

Sea Change ran throughout the demonstration on electrical power created by 12 fuel cells from Hydrogenics, now known as Accelera by Cummins. Gaseous hydrogen stored in rooftop tanks fed the fuel cells, allowing the ferry to consistently reach 10 knots during the short voyages. The only byproduct from propulsion was water clean enough to drink.

“When we were able to get hydrogen and get underway, it definitely performed as described as a viable zero-emission commercial vessel,” said Thomas Hall, a spokesperson for the ferry service. “It drew a ton of excitement from the community inside and outside of the maritime world.

“But we did find access to hydrogen is not readily available,” he continued. “There are relatively few fueling providers, and at this time, they were only able to provide gray hydrogen, not renewable, sustainable hydrogen we would expect to operate.”

The six-month demonstration ended in December 2024 as planned after a dedicated funding stream ran out. According to Hall, the ferry system has no plans to place the vessel into permanent service without additional financial support.

San Francisco Bay Ferry’s experience with Sea Change highlights the paradox facing the maritime industry in the U.S. and beyond. At this point, technology exists to transition workboats away from diesel to cleaner forms of energy. And many operators have expressed interest in moving ahead with these alternatives to reduce emissions and improve passenger experiences.

However, the costs associated with making that transition are the single biggest impediment to moving away from marine diesel. Uncertainty about fuel availability and the supply chains needed to operate with alternate forms of propulsion are a close second. These hurdles are slowing adoption at any meaningful scale.

“The biggest hurdles to adoption of non-diesel fueled vessels continue to be the availability and cost of the alternative fuels, the necessary supporting infrastructure and the capital cost of vessel construction,” said Lawren Best, director of design development for naval architecture firm Robert Allan Ltd., Vancouver, British Columbia.

It’s no accident that diesel is the dominant fuel source for workboats around the world. Diesel is energy dense, stable to transport over long distances, and abundant the world over thanks to a vast supply infrastructure. As a fuel, its primary downside is the emissions that escape from the exhaust stacks, even with scrubbers that neutralize certain byproducts from combustion.

The global push to decarbonize the maritime industry has already led to numerous advances. Liquefied natural gas (LNG) has established a foothold in the global shipping and cruise sectors. In the U.S., companies such as Seaside LNG, Spring, Texas, have already built two articulated tug-barge units to bunker big oceangoing ships, and a third unit is on order.

Biodiesel produced from non-petroleum sources such as vegetable oils or restaurant grease represents a cleaner-to-produce alternative to traditional diesel. Most engine manufacturers also warranty their engines to run on B100 biodiesel, making it an immediate replacement fuel, even though the tailpipe emissions are essentially the same as diesel.

“It is a drop-in substitution for conventional diesel and requires no vessel modifications other than perhaps a few frequent filter changes early in the changeover,” said Mike Complita, principal in charge of Elliott Bay Design Group, Seattle.

In early June, Incat Crowther, Sydney, Australia, announced plans to design a 516-passenger ferry for Catalina Express, San Pedro, Calif., that will run on R99 renewable biodiesel made from plant-based sources. The 160' catamaran will be powered by four MTU Series 4000 engines from Rolls-Royce, London, U.K., and is expected to reach speeds over 42 mph.

Biodiesel and LNG, however, are considered bridges to low- and zero-emission fuels of tomorrow, which could include ammonia, liquid or gaseous hydrogen or methanol. Each of these fuels shows promise as a low- or zero-emission alternative to traditional diesel for vessels ranging from oceangoing ships to harbor tugboats.

American companies have responded to growing interest in these alternative fuels. Caterpillar, Irving, Texas, recently announced plans to field-test its methanol dual-fuel 3500E series engines starting next year in a partnership with Damen Shipyards Group, Gorinchem, Netherlands. The engines can run on traditional diesel or methanol.

“We’re expanding the 3500E platform’s fuel flexibility to provide customers with a wider array of options to navigate the energy transition,” Andres Perez, global tug segment manager at Caterpillar Marine, said in a statement. “Fuel flexibility is key to future-proofing assets. This technology will enable owners to adopt their fuel of choice when the conditions are right without having to build a new asset or face cost-prohibitive retrofits.”

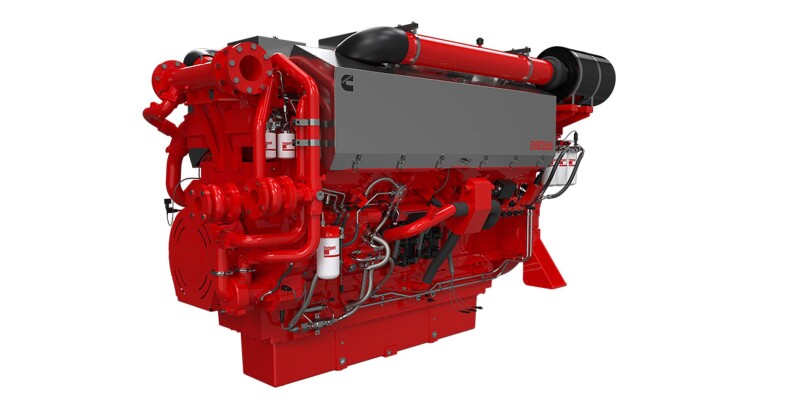

Meanwhile, Cummins, Columbus, Ind., announced in March that it had received approval-in-principle from DNV for its methanol-ready QSK60 engines in the 2,000 to 2,700 hp range. The company said kits to retrofit existing engines will be available starting around 2028, a time frame it expects to align with “market demand and infrastructure readiness.”

Multiple engine makers in the U.S. and overseas are developing dual-fuel internal combustion engines that can run on diesel as well as hydrogen as a way to reduce overall emissions. The Robert Allan Ltd. naval architect Best considers dual-fuel engines to be a viable stepping stone on the path to decarbonization. This transition, however, is not without its tradeoffs.

“As the engines become more advanced and the fuel becomes cheaper and more readily available, these engines will become more widely accepted,” said Best. “However, the reduced energy density of the future fuels and additional space required for the supporting systems means either significantly more frequent refueling or increased vessel size to achieve the same endurance as was achieved on the equivalent diesel vessel.”

Innovation around alternative fuels is not coming just from established global companies. Last fall, Amogy, Brooklyn, N.Y., announced the tugboat NH3 Kraken had successfully completed its maiden voyage powered by ammonia. The company successfully retrofitted a 105' harbor tugboat built in 1957 to run on its ammonia-to-electricity propulsion system.

Ammonia has the advantage of being widely available in ports around the world and is already accepted in sectors of the maritime industry such as fishing, where it is used for refrigeration. Amogy’s proprietary system splits or “cracks” liquid ammonia into hydrogen and nitrogen, its two base elements.

“The hydrogen is then funneled into a fuel cell, generating high-performance power with zero carbon emissions,” the company said, noting that NH3 Kraken was fueled with renewable-sourced or “green” ammonia to further reduce its carbon footprint.

Other companies are taking a similar approach, albeit with different fuels and processes. Maritime Partners, Metairie, La., known for its vast portfolio of inland towboats and tank barges, is making steady progress on the groundbreaking methanol-powered towboat Hydrogen One.

The vessel developed by Elliott Bay Design Group will feature multiple refrigerator-sized reformers that convert liquid methanol into hydrogen. Fuel cells then turn that hydrogen into electricity to propel the vessel. The system is scalable based on an operator’s power demands, and emissions from the reforming process are substantially less than traditional diesel engines.

Dave Lee, Maritime Partners’ vice president of design and innovation, said this system has several key advantages. First, methanol is a known commodity that is already transported on the U.S. inland waterways. It’s widely available in ports and well understood in the maritime community. Supply chains are growing more robust as they become a fuel source for other segments of the maritime industry. By the end of this year, shipping giant Copenhagen, Denmark, for example, will have up to 18 large, 16,500 TEU containerships capable of running on methanol.

“The one big thing about this boat and what we’re really trying to prove to the industry is that the technology works,” said Lee. “We know where the fits are for this technology and where they are not, at least not yet. This technology works awesome for an inland towboat, and it would work awesome for a refueling/bunkering boat.”

Since it was first announced in the early part of this decade, Hydrogen One has been redesigned to accommodate larger reformers, which in turn allows the vessel to generate more power. After reaching a critical design agreement with the Coast Guard last spring, Maritime Partners expects to begin the process of selecting a shipyard to build the vessel this fall, Lee said.

Complita, with Elliott Bay Design Group, acknowledged that the pace of adoption for some alternative fuels feels slower than some might have expected just a few short years ago. He sees operators waiting on the sidelines as technology matures, supply chains materialize, and a single alternative fuel emerges as a dominant counter to diesel.

“The rate of change is still moving just as fast as it was a few years ago, and in fact, it might be moving even faster today,” he said. “What’s different is the perception around the rate of change.

“Think about this transition relative to diesel engines,” Complita continued. “They started out very nasty but have been refined over 100 years to the very clean engines we have today. We are going through the same evolution with alternative propulsion. It’s just that we all want it to happen today.”