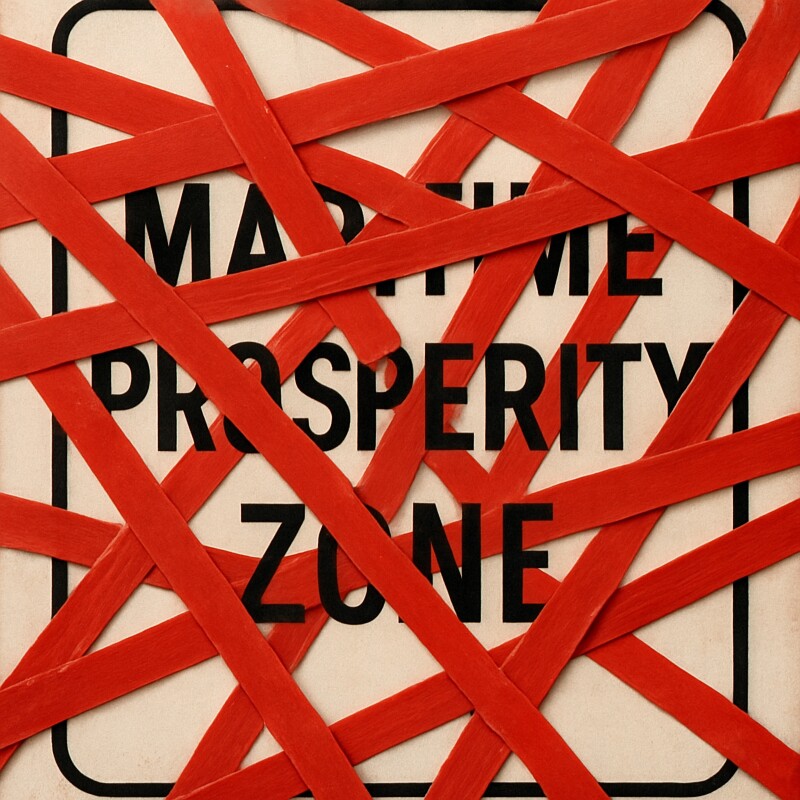

American mariners cheered in early April as President Trump introduced “maritime prosperity zones.” Included as part of the much-ballyhooed Restoring America’s Maritime Dominance executive order, maritime prosperity zones are intended to “incentivize and facilitate domestic and allied investment in United States maritime industries and waterfront communities.”

With stipulations for regulatory relief and favorable terms for capital investment, these new maritime prosperity zones will be a real help in unlocking new facilities and refreshing old waterfront shipbuilding infrastructure.

It sounds great. But the details are a mess.

First, the laws supporting the executive order are in flux. The legislative backing for the executive order was opportunity zone legislation from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, which means, in essence, that maritime prosperity zones can only be established in impoverished harbor zones that meet the low-income criteria necessary to qualify as an opportunity zone.

That makes no sense.

Maritime prosperity zones need to be placed in the most strategically sensible areas of the country, and in waterfront areas that may have real, unmet potential. The forthcoming Shipbuilding and Harbor Infrastructure for Prosperity and Security (SHIPS) for America Act allows for that kind of strategic leeway, designating the Marad administrator to be the primary designator of maritime prosperity zones.

But the SHIPS Act is still mired in Congress, and waterfront stakeholders can’t afford to wait.

An opportunity zone refresh is contained in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, but it leaves waterfront stakeholders with a tricky bureaucratic challenge.

In the executive order, the secretary of commerce is set to define the qualifying parameters for a maritime prosperity zone, but again, maritime prosperity zones may only be targeted to census zones that meet certain poverty or geographical criteria.

There’s no guarantee that the secretary of commerce’s definition of a maritime prosperity zone will align with how states define and select their opportunity zones.

The administration has some work to do before it identifies new maritime prosperity zones. In short, poverty should not define an area’s eligibility to serve as a maritime prosperity zone. Strategic potential and maritime utility should be the leading factors in identifying sites for future maritime prosperity zones, with poverty levels relegated to a far less important discriminator.

The maritime prosperity zone concept is a great idea that risks being run aground by sloppy execution. Mariners — not economists — should be identifying maritime prosperity zones. Going forward, it would be a real shame to penalize potentially ideal shipbuilding sites because they’re on the wrong side of an arbitrary median income cut-off. It’s time to pick good sites and support them.