An underwater construction crew working at a depth of 50 meters (164') for more than a few days will most likely participate in something called “saturation diving.” The divers live in a pressurized habitat on the surface or near the worksite for up to 28 days.

The habitat is pressurized to match the underwater depth so the divers’ bodies become “saturated” with inert gas. The divers use a pressurized diving bell to travel to and from the worksite and avoid the need for daily decompression sessions because their body pressure remains constant. When the work is completed, the divers undergo one slow, controlled decompression in the habitat, which can take several days.

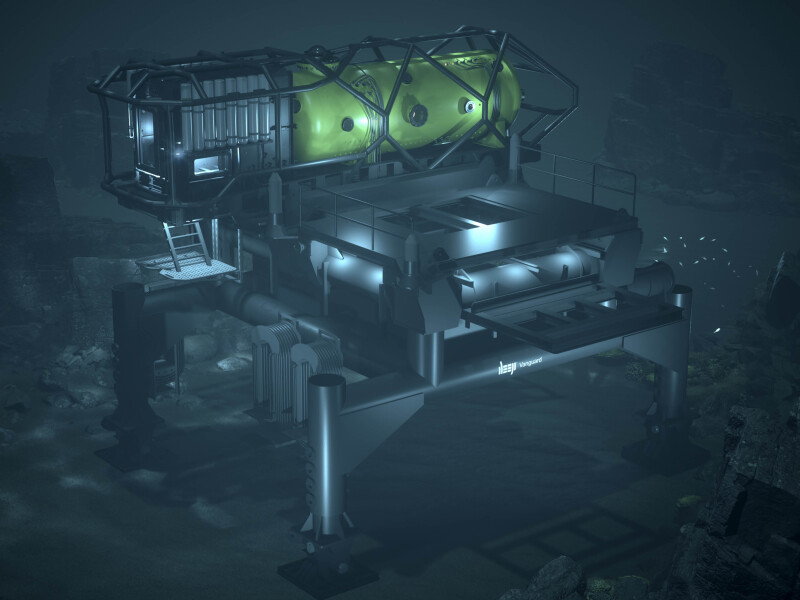

DEEP, an ocean engineering and technology company based in the United Kingdom, has recently expanded into the United States and is building open-ocean subsea habitats for human occupation. The first one, Vanguard, is designed for weeklong missions supporting projects like coral-reef construction, technical diving training, and ocean science.

“If a diver is working at 50 meters on a wind farm, for example, the diver is going to have five to 10 minutes of actual bottom time and then you’re going to spend a disproportionate amount of your time decompressing on that way up,” said Sean Wolpert, a member of the DEEP board of directors and former president of the company.

“This would be a perfect application for Vanguard because you can position the habitat in the middle of that wind farm and go down there and stay at that equilibrium. If you’re down at 50 meters, that’s six atmospheres. Rather than five to 10 minutes, you can go down there and stay for days.”

He said that DEEP focused on the ocean because the overall undersea environment has not received the attention the firm feels it should get. “Bringing the scientific chain down to the seabed, providing that permanent presence, that fluid access to the seabed, was something that was needed, and we felt like that would be a game changer for humanity,” said Wolpert.

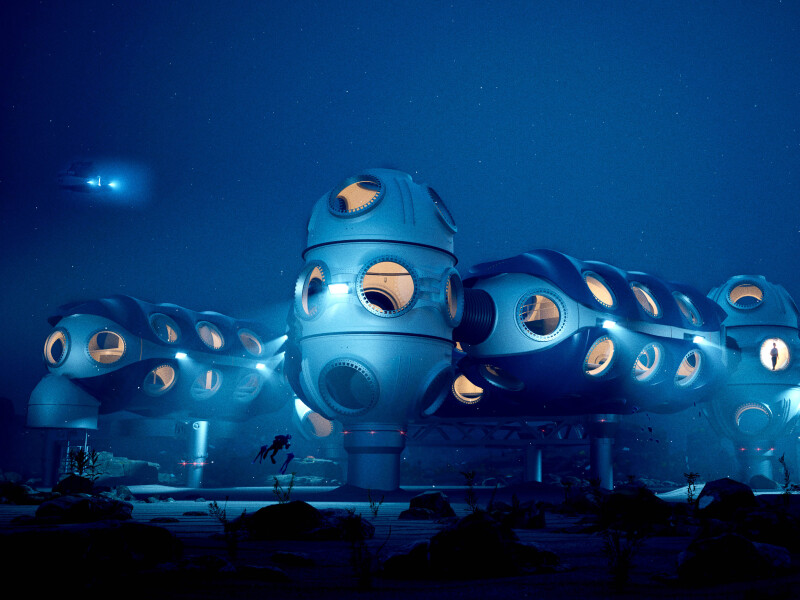

He continued, “When the international space station went up in November 2000, that drove research, capital expenditure, and innovation. We felt that we could apply our ocean technology and capabilities to create next-generation subsea human habitats.”

Wolpert called the ocean the most complex dynamic ecosystem on the planet but said only 20% of it has been mapped. “We’ve only discovered 15 to 20 percent of the species and organisms we believe to be in the ocean,” he added.

GENERATING INTEREST

Vanguard is being constructed on land in Florida, and DEEP has partnered with Triton Submarines, Sebastian, Fla.; diving and marine services company Unique Group, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates; and with engineering firm Bastion Technologies, Houston. DEEP said its expansion into the U.S. represents a $100 million investment. Wolpert said Vanguard is expected to be completed by the end of 2025. It can be deployed at a maximum depth of 164' and houses up to four people.

Best described as a portable underwater bunkhouse, Vanguard has an open layout and viewing ports. A larger unit called Sentinel can go down 200 meters (656') and has individual living areas for up to six people.

“It’s not the Four Seasons, but it will be something that doesn’t drain you mentally and physically as if you were in a conventional saturation diving bell system,” said Wolpert.

As people have learned about DEEP’s products, interest has come from unexpected sources, Wolpert added.

“As we explained what Vanguard can do, we found that there was a lot of interest from the academic and science community, even over to the defense sector,” he said.

The habitat consists of three main parts: the foundation, the living chamber, and the wet porch. The foundation and living chambers are self-explanatory, while the wet porch is where a diver can enter and exit for daily missions. A submarine will link to the habitat and deliver passengers through a dry passage system. Sentinel is a modular design, and as long as the maximum depth isn’t exceeded, more sections can be added. Sentinels are designed to be re-deployable, but because of their size, they stay in place for a longer duration.

“With the habitat, you go down once, and then you come up once, so it allows you to be productive,” said Wolpert. “You’re getting your work done over a smaller number of days, and you’re de-risking the whole decompression of things.”

In addition to the wind-farm example, Wolpert said that undersea infrastructure like pipelines and data cabling could be ideal uses for DEEP habitats. “Subsea data cables process $10 trillion of transactions every day,” he said. “Pipelines move around 50-plus percent of the natural gas and oil that gets consumed, so saying they’re critical is an understatement.”

In September, a cable in the Red Sea was cut, disrupting internet traffic for Asia and the Middle East. Having a surveillance presence could help incidents like this. A DEEP habitat could provide hubs for underwater drones where they could be charged and serviced. “Then what you have is a genuine deterrent,” said Wolpert. “It’s the Hawthorne Effect, when you know that you might be watched, you alter your behavior.”

For research on things like hurricanes and other weather phenomena, the habitat exteriors could be fitted with data-acquisition equipment that could be released like the Dorothy device in the movie Twister.

SAFETY FOCUS

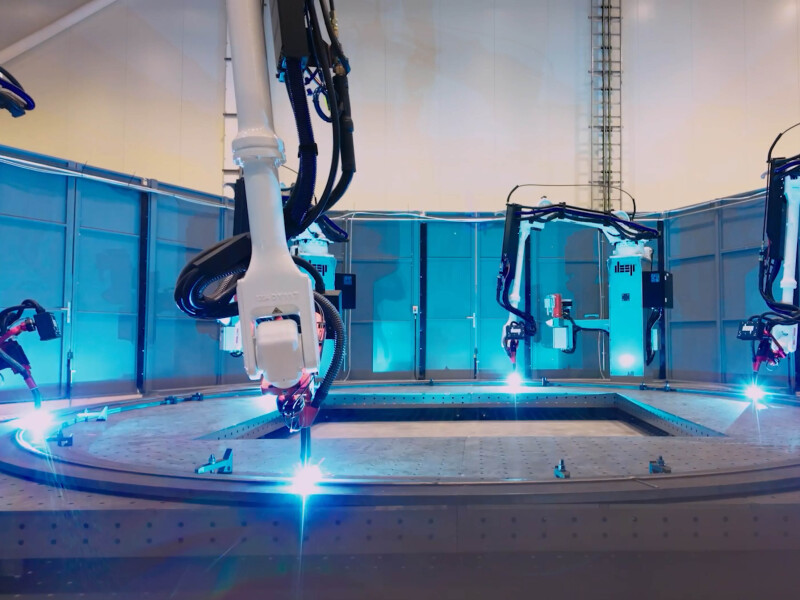

The habitats are constructed from steel covered in Inconel cladding for added strength. Inconel is made with a family of high-strength nickel-chrome alloys and is used in high-heat and aggressive-chemical environments. DEEP developed its own 3D printing process for making the habitat components. Originally, the company was going to use conventional processing methods, but the pandemic disrupted supply chains and the geopolitical climate, so DEEP deployed the new technology called Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing.

“It shifted our product development timeline and training timeline too far to the right,” said Wolpert. “There were too many unknowables and conditionalities for us. We wanted to be able to develop this swiftly so we had engineers find a solution.”

Peter Richards, CEO of DEEP Manufacturing, and his team saw an additional commercial opportunity with the new process and the company spun off the business as a wholly owned subsidiary.

Vanguard and Sentinel need to be built to the highest standards to sustain life underwater. DEEP worked closely with international certification and classification provider DNV for underwater technology.

The Vanguard components have passed a factory acceptance test, a harbor acceptance test, and a sea acceptance test.

“We worked for years on the designs and engineering and manufacturing,” said Wolpert. “We got these components classed to make sure that we’re not marking our own homework, so an independent body who’s skilled in this comes through and says, ‘You have done this in a sound way.’”

While DEEP said it will not tell people how to use the habitats, it will restrict someone that doesn’t have the appropriate training. “If you haven’t SCUBA dived, you’re probably not going to go down there,” said Wolpert. “We have leading naval divers working with us to drive forward excellence from an operations perspective and in terms of better preparing the divers.”

He continued, “The other element is that you can’t just take four people and go down. We will always have a DEEP commander that will be there ... to make sure that safety is paramount.”