A newly issued compendium of National Transportation Safety Board marine investigations looks at a wide range of marine casualties, and a few common mistakes emerge from those stories.

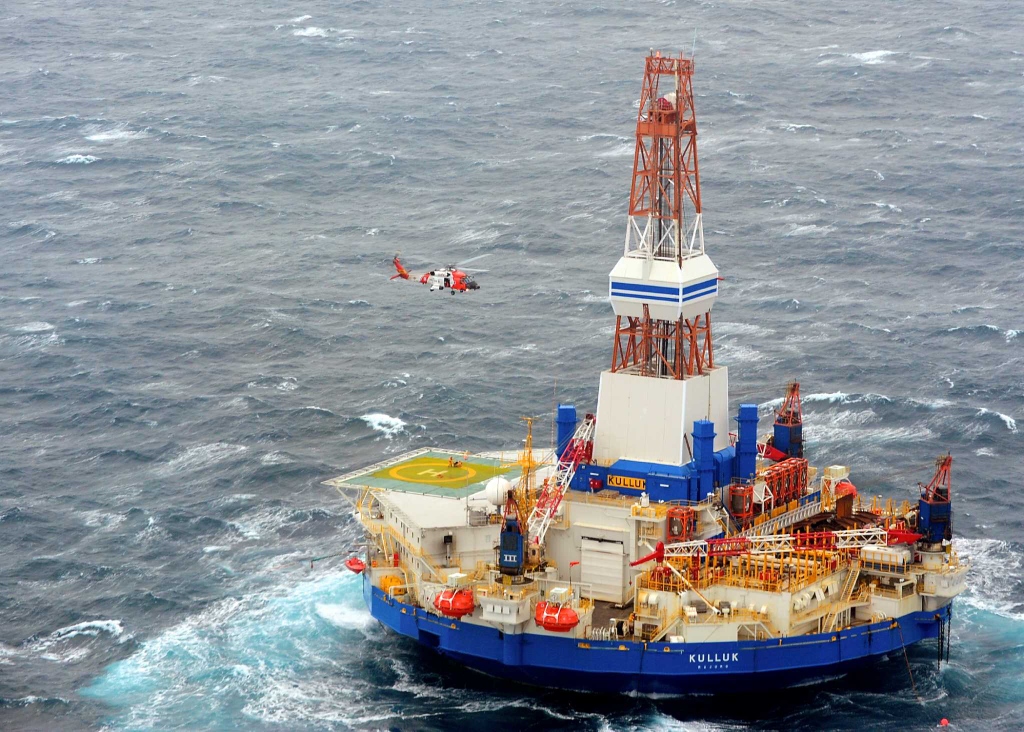

The Safer Seas Digest 2015 summarizes 29 cases from recent years. They range from the high-profile, like the Dec. 31, 2012 grounding of the Shell Offshore Inc. mobile offshore drilling unit Kulluk in Alaska.

Then there were incidents like the July 1, 2014 sinking of the towboat Jim Marko near St. Louis, Mo., when the operator underestimated danger from hull damage, and open watertight doors did the rest. But it could have been much worse, the NTSB authors note in the report’s “lessons learned” section:

“Crewmembers should wear appropriate personal protective equipment for operations under way and always wear personal flotation devices when abandoning ship. When the towing vessel Jim Marko sank in the Mississippi River, two crewmembers were barefoot and one did not wear a personal flotation device. The river was experiencing high-water conditions at the time, which would have posed a heightened risk had crewmembers been forced to abandon ship into the water.”

Failure to keep adequate lookout while leaving the helm on autopilot was a factor in a couple of 2014 cases from the Gulf of Mexico, when one OSV ran into a natural gas production platform, and another hit a shrimp boat. It is such a recurring problem in the Gulf’s oil patch that the Coast Guard this week issued a marine safety alert warning against over-reliance on automatic steering systems.

The report notes that vessel stability, and masters’ understanding of it, is still a serious issue in the commercial fishing industry – one the NTSB and Coast Guard have been trying to improve since a series of sinkings in 1999.

Other takeaway lessons from the NTSB findings include:

Voyage planning: Before getting under way, vessel crews should develop a voyage plan covering the entire voyage from dock to dock. The plan should outline courses, expected times of course changes, transit speeds, available aids to navigation, and alternative routes or areas of refuge. It should also identify hazards to navigation along the intended route, considering factors such as restricted waters, traffic separation schemes.

Communications: Effective communications are essential to safe operations, particularly during emergencies or close maneuvering situations. Before each voyage, vessel crews should develop a communications plan to include both internal (i.e., between watchstanding locations) and external (i.e., between vessels) communications, primary and backup communication systems, a list of stations or vessels using the systems, and procedures for switching between the systems in the event of a failure. Also, before engaging in any operation that involves an increased risk, vessel crews should discuss information expected to be shared during the operation along with emergency procedures.

Fatigue: Across all transportation modes, the NTSB ranks reducing fatigue-related accidents among the top ten safety improvements on its latest Most Wanted List. Effective ways to prevent fatigue include hours-of-service limits, predictable work/sleep schedules, and consideration of circadian rhythms in shift scheduling.

Alerting and navigation alarms: Alarms can be effective tools in ensuring alert and vigilant watchstanding. These alarms can be based either on time, by sounding at preset intervals that require action by the watchstander, or on proximity, such as depth sounders, GPSs, or radar indicators. Owners and operators should implement written procedures for their configuration and use, and watchstanders should be familiar with their functionality. However, these alarms should not substitute for the management and mitigation of fatigue.

Written procedures and training: The failure to take proper action to prevent or mitigate an emergency can often be traced to the absence of specific written procedures and a lack of training.

Watertight integrity: Maximizing the watertight integrity of a vessel is critical to buoyancy and stability in the event of a marine casualty. A hole in the side shell of a vessel, especially near the waterline, poses an immediate risk. When a potential hull breach has been identified, operations should be halted until repairs are made or the crew determines that the damage does not affect seaworthiness. For systems that source from or discharge to the sea, an effective lock-out/tag-out program helps to prevent inadvertent flooding associated with repairs. In addition, watertight doors should be kept closed at all times when a vessel is under way, unless a crewmember is passing through. A lack of watertight integrity contributed to the complete loss of six vessels during the NTSB’s reporting period.