Two events last weekend served to highlight the importance of the marine industry during emergencies and disasters. The first was Sunday’s 15th anniversary of 9/11 and the second was the opening of “Sully,” the story of the 2009 emergency landing of a commercial jet in New York’s Hudson River.

The heroic efforts of firefighters, police officers and other rescue workers during the 9/11 disaster, has been well documented. But another group, commercial mariners, also played an important role that day, rescuing thousands of people trapped at the southern tip of Manhattan Island. Virtually every kind of small vessel responded to the Coast Guard’s call for all boats in the vicinity to converge on the Battery Park area, located just a few blocks south of the World Trade Center. A huge fleet made up of tugs, ferries, sightseeing vessels, police launches, fireboats, Coast Guard rescue vessels, all seven Corps of Engineers New York District vessels, and a smattering of recreational craft converged on the area. The Coast Guard estimated that anywhere from 500,000 to one million people were evacuated from Manhattan by boat.

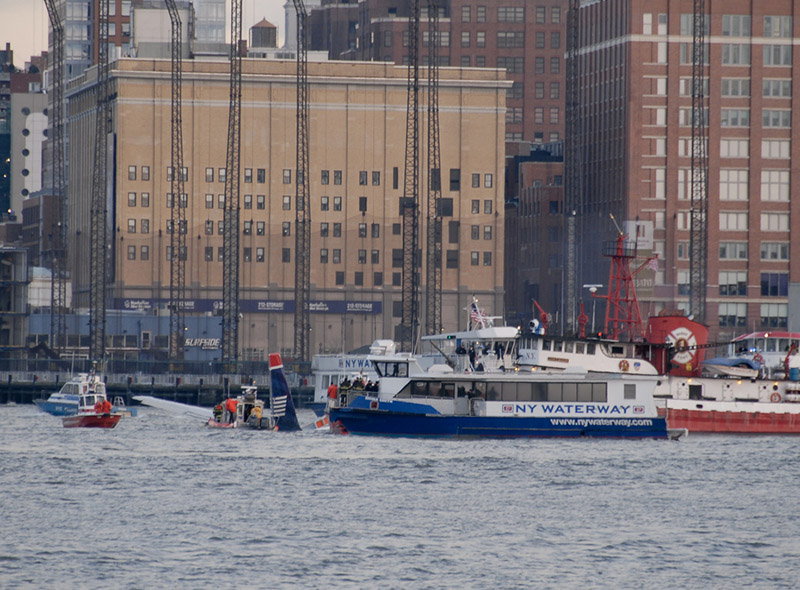

Mariners were also quick to help when Capt. Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger had to ditch US Airways Flight 1549 in the icy Hudson River in January 2009. Once his aircraft was down, he had an untold amount of training and experience from the harbor’s maritime industry at his side. Immediately after the airliner came to rest, at least a dozen vessels were on scene — with more to come. New York ferry operators boldly pressed in, fighting strong currents and plucking scores of people from the plane's wings. An incredible 14 New York Waterway ferries rescued 142 of the 155 passengers. The company’s founder, Arthur E. Imperatore, reported that his ferry captains and deckhands did not wait for orders to respond.

Three separate ferry operators were on the scene in minutes. The Circle Line Manhattan ferry hurried its paying passengers off so that it could load and rush police and fire department resources to the landing site. The sheer volume of the response was unique to the maritime industry and particularly characteristic of the New York maritime community.

“We sent a boat immediately to see if we could help,” Harold Smith, supervisor, Miller’s Launch, Staten Island, N.Y., told WorkBoat after the 2009 incident. “It’s not about the work. It’s about everyone pulling together to help. It’s a great thing to see. I haven’t seen such a big turnout since 9/11, and that made me proud to be a mariner in New York Harbor.”

Andreas Sappok, general manager of Circle Line Sightseeing Cruises, said reaction to the emergency came down to a basic human instinct. "They’re people in need, and you want to help,” he said. “It's very simple."

As John Fulweiler wrote when he reported on the incident for WorkBoat in the March 2009 issue, “It was the immediacy and sure-footedness of the commercial mariners’ response that is most impressive. What other private industry can boast of such overwhelming expertise and enthusiasm brought by its members in moments of crisis?”