Plans to build hundreds or even thousands of offshore wind turbines off the U.S. East Coast “will be the biggest change to the sea floor in the area since the last Ice Age ended about 14,000 years ago,” according to scientists.

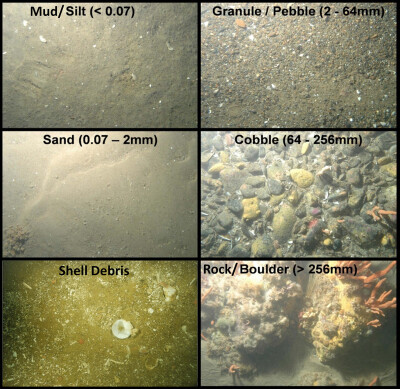

Around 20 offshore wind lease areas are now planned for mainly soft bottom of sand or mud, with scattered hard substrate of gravel, cobble and rock, according to their recently published study.

As wind turbine arrays are built, they will add massive steel towers, electric power cables, and millions of tons of rock to protect the new industrial infrastructure.

“Wind farms will add a lot of hard structures to these areas, potentially altering the habitat and species that inhabit these areas, which will likely affect fisheries,” wrote the research team led by Kevin Stokesbury, dean of the School for Marine Science & Technology (SMAST) at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth.

In its natural state, “the sand will move around but it doesn’t change the community” of marine life living there, said Stokesbury. Off the Mid-Atlantic coast particularly, the wave-swept sand bottom “is like the Great Plains before development,” he said.

Imposing lots of artificial hard structures could be a change similar to that of the last ice age in the Northeast, when glaciers plowed rock debris and left it in patches on today’s sea floor off New England, said Stokesbury.

The study “Anticipating the winds of change: A baseline assessment of Northeastern US continental shelf surficial substrates” was published July 25 in the journal Fisheries Oceanography. As the title suggests, the project’s goal is to present a comprehensive picture of what the sea floor looks like now, before more wind projects are built.

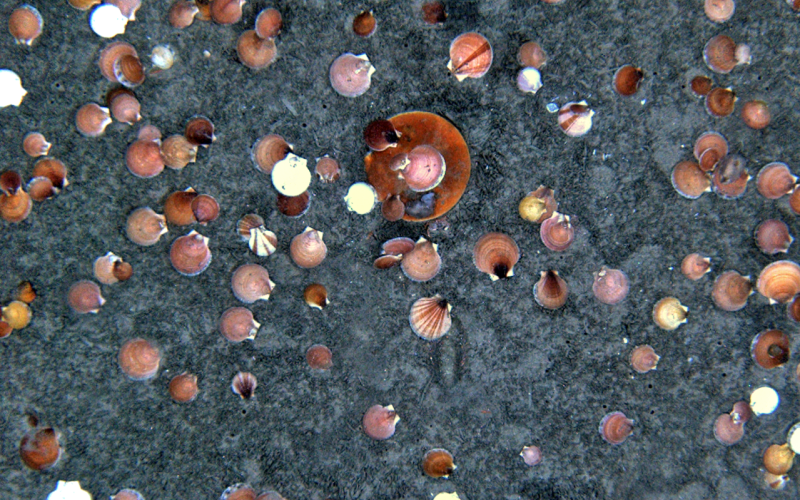

Researchers tapped U.S. Geological Survey data from “grab samples” of the sea floor dating back to 1966. Another source was imagery from “drop camera” surveys of the bottom, conducted since 1999 by Stokesbury and other UMass researchers working with scallop fishermen to help assess the shellfish stock.

“We’ve published over 40 papers on scallops,” said Stokesbury.

The scallop drop camera survey images include 242,949 samples from 2003 to 2019, and were combined with the USGS databases counting 27,784 seafloor samples from 1966 to 2011. The researchers used that to derive maps of likely surface substrates on the ocean bottom, from Virginia Beach north to the Gulf of Maine and out to the 300 meter (984 feet) depth – 84,390 square miles of sea floor all told.

In a summary of the project, the researchers say “wind farms will add a lot of hard structures to these areas, potentially altering the habitat and species that inhabit these areas, which will likely affect fisheries. The maps created in this study will help us monitor changes to the substrate after wind farm construction. This will provide a more comprehensive view of the impacts of offshore wind on ocean ecosystems.”

Earlier in his career as an environmental scientist, Stokesbury did research on the aftermath of the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill off Alaska. He said a big question for scientists assessing the impact of that accident on the regional environment was “what was it like before, and how do you measure that?”

Effects of emplacing turbine towers and other hard structures off New England would create habitat favorable to some fish species, like black sea bass, already extending their range up the East Coast with warming ocean temperatures.

That’s been considered good news by some recreational fishermen, who have been making good catches around the Block Island Wind Farm’s five turbines built in 2016. But as with any changing habitat, “there’s going to be winners and losers,” said Stokesbury.

Commercial fishermen also worry about invasive species colonizing the turbine arrays. Scallop fishermen see potential for starfish and other shellfish predators.

There will be more new material than just turbine towers in the water. Each turbine will have more than 22,000 square feet of rock scour protection piled around the base of each monopile tower, with dozens of miles of power cables buried in the sea floor or protected with additional rock cover.

The study looks to the history of offshore oil drilling in the Gulf of Mexico. The researchers point out area never-answered questions about what the installation of almost 7,000 structures since 1942 – and 3,200 still operational – did to change the Gulf’s environment.

“Within weeks of constructions, plants and invertebrates begin to attach to these platforms, and in the following months and years, a highly complex food chain was created with each platform seasonally serving as habitat for fish densities 20 to 50 times high than the surrounding open water,” the researchers wrote. “Invasive species also colonize these platforms very successfully, providing a steppingstone for their spread.”

Reusing old oil rigs as artificial reefs benefitted the recreational fishing industry, they note.

“This suggests a significant change in the Gulf of Mexico ecosystem, but was it? What were the components of the original Gulf of Mexico ecosystem and did their makeup change? Was there a significant increase in hard substrate? Did these platforms create new complex food chains, enhance existing food chains, or only serve to concentrate and spatially reallocate existing food chains?” the researchers said. “With no baseline data collected in a scientifically rigorous design prior to 1942, these questions will remain unanswered.”

Today, “the Northeastern U.S. continental shelf now faces a similar installation agenda with the burgeoning offshore wind industry driven by the dire consequences of global warming coupled with advances in engineering,” the study says.

“If implemented, the proposed wind farms would introduce new hard structures…in locations presently dominated by mud, sand, and shell debris, thereby increasing the availability of stable, hard substrates in locations where they are extremely rare or do not exist.”

“Large tracks of open uniform sand with shell debris accumulated over centuries What the creation of a windfarm will do is change the ecosystem by adding hard substrate as well as intertidal and subtidal zones that support new and possibly invasive species, instead of the original continental shelf ecosystem.”