With the recent publication of Chevron’s 10-K annual report to the Securities and Exchange Commission and the proxy for the upcoming Hess merger, Wall Street is pondering the impact of the disclosure of ExxonMobil’s declaration of its right of first refusal contained in the Joint Operating Agreement for the Guyana oil field.

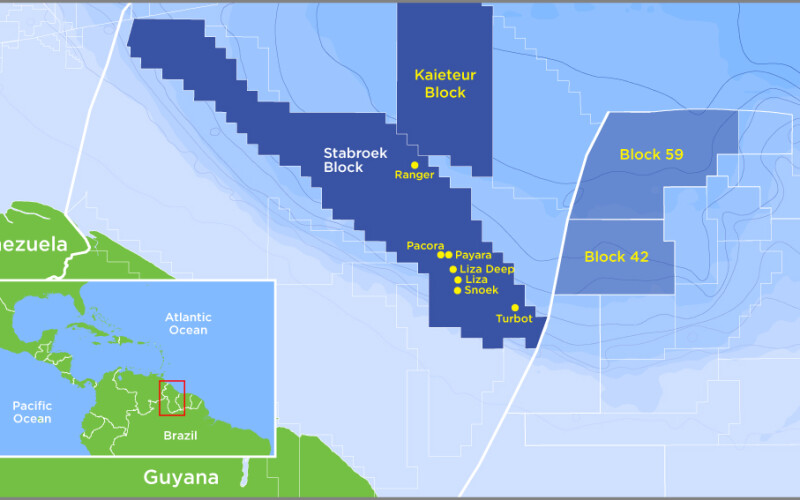

Stock price reactions suggest Wall Street is watching but not acting, after knocking down Hess’ share price upon the disclosure. At issue is Hess’ 30% interest in the huge Guyana oil deposit it is developing in partnership with ExxonMobil and Chinese national oil company CNOOC.

Partnership developments are traditionally done under JOAs which spell out the responsibilities and obligations of the respective parties involved. As the expression “too many cooks in the kitchen” suggests, the operating partner is assigned responsibility for most decisions but it cannot run the project without approvals of key decisions by the partners.

Usually, JOAs have provisions governing the ownership group. This means that if a partner wants out of the JOA by selling its interest, provisions govern how that works such as the right of the other partners to purchase the interest (right of first refusal). The existing partners must approve a new partner if they do not exercise an RFR, and the new partner must agree to the JOA terms.

This issue involves the language of the JOA for Guyana and whether the right of first refusal is triggered by the acquisition of Hess by Chevron. Is this a “change of control” transaction under this JOA triggering ExxonMobil’s rights or is Hess as a division of Chevron the same partner?

The dispute has now reached the legal battle stage with ExxonMobil filing for arbitration. If determined to be a change in control, Chevron likely will abandon the Hess acquisition. The complicating factor is that the Guyana interest is the bulk of the value of Hess in the acquisition.

The arbitration case will delay the closing of the Hess/Chevron deal. The investment community is wondering about ExxonMobil’s motivation to raise the issue since it could leave the operating group intact with Hess being financially richer. However, ExxonMobil might decide it wants to acquire Hess after it completes its Pioneer Natural Resources deal. The answer lies in the arbitration case outcome, but understanding ExxonMobil’s motivation is critical for Wall Street.

ExxonMobil, as the discoverer and operator of the Guyana project, knows the most about its potential size and value. They likely assessed Chevron’s valuation as too low, which drove their action. For ExxonMobil, the opportunity to acquire more of a known crown jewel oil reservoir may be worth upsetting the Chevron/Hess deal.

ExxonMobil also may be motivated by the “bird in the hand is worth two in the bush” idiom. How many potential Guyana-size fields remain to be found? We understand ExxonMobil is pessimistic about the number. Maneuvering for a greater share of Guyana may be a prudent financial move, albeit with an uncertain timeline.

The offshore industry should be paying attention to this deal. ExxonMobil’s ultimate move may say something about the long-term future of offshore exploration and development. Or at least what the industry’s largest company thinks.