The Maine groundfish trawler Emmy Rose with her crew of four, lost in November 2020, probably capsized when water collected on the aft deck and downflooded the vessel through unsecured deck hatches, the National Transportation Safety Board reported.

The agency’s accident report calls for the Coast Guard to ensure that commercial fishing vessel safety examinations include inspection of hatch covers to determine if they are watertight and adequately secured.

Covers on freeing ports – openings around a vessel’s main deck to drain water off – must likewise be inspected to make sure covers are constructed to allow water to readily flow outboard, as intended, and not inboard, the report says.

The NTSB reiterated its call for mandatory personal locator beacons to be carried by commercial fishermen and other mariners. Essentially pocket EPIRBs, PLBs signaling to satellite networks can guide rescuers to individual survivors at sea.

Coming after the El Faro cargo ship disaster in 2015 with 33 lost, and the 2019 Scandies Rose fishing vessel sinking in Alaska with five lost, the Emmy Rose was the latest example of how PLBs could have led rescuers to missing mariners.

“It shouldn’t take three marine tragedies to recognize the vital importance of personal locator beacons,” said NTSB Chair Jennifer Homendy in a statement announcing the Emmy Rose report. “Given their wide availability and relatively low cost, I urge all fishing vessel operators to provide crewmembers with PLBs today – don’t wait for a mandate from the Coast Guard. If the Emmy Rose crew had access to these devices, perhaps some of them would still be with us today.”

Captain Robert Blethen Jr. of Georgetown, Maine; Jeff Matthews of Portland, Maine; Ethan Ward, of Pownal, Maine; and Mike Porper, of Gloucester, Mass. and Peaks Island, Maine, were never recovered. The crew was inbound for Gloucester, Mass. to deliver their catch when the Coast Guard in Boston received an automated distress message at 1:30 a.m. Nov. 23 from the Emmy Rose’s emergency position indicating radio beacon, about 27 miles off Provincetown, Mass.

Searchers using side scan sonar found the sunken Emmy Rose nearly 800 feet down in May 2021, about 3.5 miles from the EPIRB reported sinking. In September 2021 a remotely operated vehicle was used to survey the wreck.

NTSB investigators concluded that two freeing ports, designed to drain water off the Emmy Rose’s deck, were closed. Water accumulating on deck “caused the vessel to list starboard, further reducing the Emmy Rose’s already compromised stability,” the agency reported.

“Although investigators could not definitively determine the source of initial flooding, it most likely began through the lazarette hatch’s cover, which did not have securing mechanisms and therefore could not be made watertight,” according to the NTSB.

“That allowed following seas – seawater that flows in the same direction as the vessel – and accumulating water on deck to flood down into the lazarette, a compartment below the deck in the aft end of a vessel.”

Working with analysis from the Coast Guard Marine Safety Center, NTSB investigators “found that at the time of the sinking, the Emmy Rose likely did not meet existing stability criteria, making it more susceptible to capsizing,” the agency said. The vessel was at increased risk from sea conditions on its return course toward Gloucester, with east-southeast winds and quartering seas that put water on the aft working deck.

The NTSB concluded “that the probable cause of the sinking of the fishing vessel Emmy Rose was a sudden loss of stability (capsizing) caused by water collecting on the aft deck and subsequent flooding through deck hatches, which were not watertight or weathertight because they had covers that did not have securing mechanisms, contrary to the vessel’s stability instructions and commercial fishing vessel regulations.”

The 82-foot Emmy Rose was wrapping up its trip Nov. 22, when captain Robert Blethen Jr. called to their destination in Gloucester to report they had about 45,000 pounds of fish and expected to arrive at around 6 a.m. the next morning, according to an NTSB narrative of the accident. After fishing for another four hours the Emmy Rose got underway at about 6:30 p.m. for Gloucester at about 7 knots, its typical transit speed.

The National Weather Service forecast that evening called for southeast winds at 15 to 20 knots with gusts up to 25 knots, and seas 5 to 8 feet, with patchy fog and a chance of showers after midnight.

“Throughout the evening, crewmembers used the vessel’s satellite phone to communicate with shoreside contacts,” the NTSB report notes. At 6:48 p.m., “one of the deckhands called his girlfriend and told her they completed fishing and were headed to Gloucester to unload the catch. He said he was at the helm but was being relieved to go to sleep.”

“The girlfriend told investigators that the deckhand said, ‘It was the biggest catch they had ever had,” and she heard other crewmembers in the background ‘laughing, giggling, and so excited to be coming home.’”

At around 11 p.m. the Emmy Rose passed within 1.3 miles of the fishing vessel Blue Canyon, then maneuvered away from the Blue Canyon and continued on its course for Gloucester at 7 knots, according to the NTSB report.

The captain of the Blue Canyon told investigators that he did not communicate with the Emmy Rose crew, and believed he saw crewmembers moving about the aft deck under illuminated deck lights as the boats passed.

At 1 a.m. on Nov. 23, the Emmy Rose was identified on the National Marine Fisheries Service vessel monitoring system to be 27 miles northeast of Provincetown, on a course of 277° at 7 knots. This was the last VMS position transmitted by the Emmy Rose.

At 1:29 a.m. the Coast Guard Rescue Coordination Center in Boston received an alert from the emergency position indicating radio beacon (EPIRB) registered to the Emmy Rose. This initial “unlocated first alert” position was about 2.4 miles southwest from the 1 a.m. VMS position of the Emmy Rose.

Coast Guard watchstanders notified the vessel’s shoreside manager in Maine, and he attempted several times to contact the crew of the Emmy Rose on the satellite phone and via email, but there was no response.

During the next three hours, over a dozen subsequent signals were transmitted as the EPIRB drifted toward the northwest until it was recovered by the Coast Guard. There were no VHF radio transmissions received from the Emmy Rose.

At 1:54 a.m. the 210-foot Coast Guard cutter Vigorous was diverted from its location about 12 miles from the last known position of the Emmy Rose to assist with search and rescue efforts. At 2:28 a.m., the Coast Guard launched an MH-60T helicopter from the Cape Cod air station. Both arrived at the Emmy Rose’s reported EPIRB position and began searching about 3 a.m.

Within minutes the helicopter crew located an inflated life raft and notified the cutter crew of its position. The cutter crew launched a rescue boat crew and found no crewmembers in the life raft. They reported a “strong scent of diesel” in the area.

At 3:26 a.m., the helicopter crew located the Emmy Rose’s EPIRB about 500 yards from the life raft in a debris field with a fish tote and other small objects. Throughout the early morning hours, the Coast Guard deployed a 47-foot motor life boat and a fixed-wing aircraft to search for survivors.

The searchers found an estimated 600-foot oil sheen, and later that morning recovered the EPIRB, life raft, one life ring, and two wooden fish hold hatch covers. After searching over 2,200 square miles over a 38-hour period, the Coast Guard suspended search efforts shortly after 5 p.m. Nov. 24.

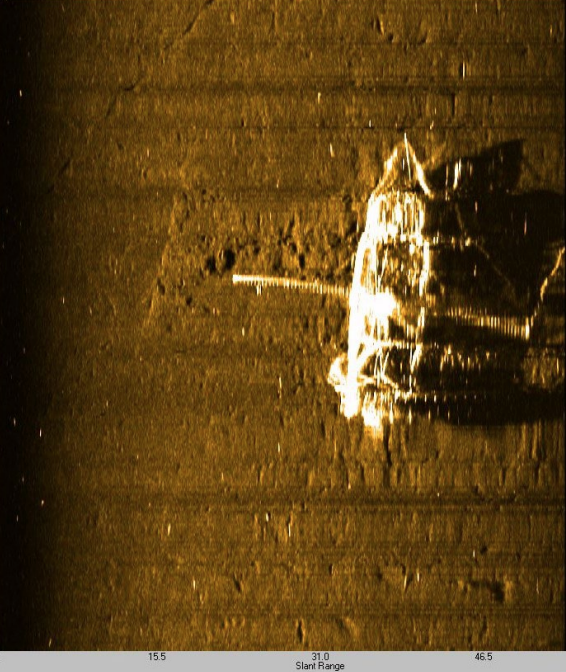

In May 2021 investigators contacted MIND Technology to conduct a side scan sonar search to locate the sunken Emmy Rose on the seafloor and assess its condition. Two side scan sonars were brought aboard the NOAA research vessel Auk for the search.

On May 19 the Emmy Rose was located about 3.5 miles west of the last VMS position at a depth of 794 feet. Side scan images were taken with different frequencies and at different heights above the seafloor. The images were interpreted by specialists from MIND Technologies. A survey reported provided to investigators stated that the Emmy Rose was found “sitting upright on the seafloor with the bow oriented at 135° (southeast direction) and both outriggers fully deployed.”

The position of both paravanes leading forward of the vessel indicated to the specialists that “the stern sunk to the seafloor before the bow at least just before the vessel made contact with the seafloor.”

With the sonar imagery in hand, the Coast Guard and NTSB asked the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute to conduct a remotely operated vehicle survey of the Emmy Rose and provided the WHOI with the location, depth of the vessel, and high-resolution imagery from the side scan survey to support planning.

On Sept. 21, an ROV and associated equipment were loaded aboard the Coast Guard cutter Sycamore in Newport, R.I.

“The ROV inspected the condition of the freeing ports. On the port side of the vessel, the aftmost freeing port was open. The next freeing port forward was closed. The next freeing port forward was partially open and had its plate hanging through the port,” the report notes.

“The remaining freeing ports on the port side were open. On the starboard side, the two aftmost freeing ports were closed. The next two freeing ports forward were open, and both had chain and lines hanging out of the ports. The starboard freeing port under the wheelhouse was open. The freeing ports under the outriggers were not able to be accessed by the ROV for inspection.”

In summing up their findings, NTSB investigators focused on the freeing ports and deck hatches as the likely source of downflooding.

“On the vessel’s aft working deck was the lazarette hatch, which was located between the net reels on the stern and covered with a nonwatertight steel cover, which rested on the hatch’s 6-inch-high hatch coaming,” the report states.

“According to the vessel manager, the hatch cover could not be fastened in any way to the hatch coaming (e.g. with dogs or latches). Since the hatch lacked securing mechanisms, the force of waves over the transom or accumulating and sloshing seawater on deck from the conditions the vessel was likely experiencing could have displaced the hatch cover and allowed seawater to downflood through the hatch and quickly fill the lazarette through the 4-square-foot opening.”

That led investigators to conclude “that although a definitive source of initial flooding could not be determined, flooding of the Emmy Rose most likely began through the lazarette hatch’s cover, which did not have securing mechanisms and therefore could not be made watertight, allowing following seas and accumulating water on deck to downflood into the lazarette.”

The Emmy Rose report again emphasizes the NTSB’s earlier safety recommendation to the Coast Guard to require all vessel personnel be provided with a personal locator beacon.

The NTSB first issued that recommendation following the sinking of the cargo vessel El Faro in 2015 in which all 33 crewmembers perished in a hurricane off the Bahamas. The agency raised the PLBs issue again after the fishing vessel Scandies Rose sank off Sutwik Island, Alaska, in 2019.

Two of the Scandies Rose crew were rescued.

“The other five were never found,” the agency recalls in its latest report. “NTSB concluded in both investigations that personal locator beacons would have aided search and rescue operations by providing continuously updated and correct coordinates of crewmembers’ locations. The recommendation remains open.”