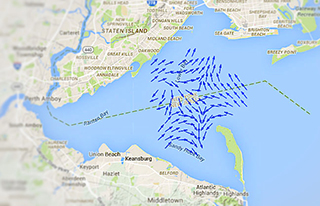

Mariners can now see tidal current direction and speed in near-real time coming from high-frequency radar stations around the lower New York/New Jersey Harbor. The new public system tracks and predicts the often tricky currents around Sandy Hook at the harbor entrance, for use by professional mariners and recreational boaters alike.

This is the third harbor system to go live, after previous public Internet connections for San Francisco and Chesapeake bays, with web access at http://tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov/hfradar/Hfscm.jsp?port=NYNJ

Current reports are generally accurate within speeds of 10 centimeters per second and 10 degrees of direction, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Spatial resolution is accurate to around 1 kilometer square in New York harbor and 2 kilometers square in the Chesapeake.

It’s the latest in a rapidly expanding global network of radars that measure sea conditions – mostly for scientific research, but increasingly for marine operations, search and rescue, and tracking pollution spills.

“We have over 130 radars along the coasts,” said Jack Harlan, program manager for NOAA’s Integrated Ocean Observing System radar network.

“This started back in 2005. There were about 30 to 40 radars situated around the country, all owned and operated by academics,” Harlan said. “We basically leveraged all that hardware, by offering a one-stop shop where they could send and share their data.”

By serving as the digital hub, NOAA does not need to buy and operate the radars stations itself. The latest harbor service draws on radar feeds from New Jersey’s Rutgers University, which operates stations around the lower harbor as part of a cooperative mid-Atlantic network with other universities.

“We can cover Cape Cod to Cape Hatteras on a consistent basis,” said Hugh Roarty, research project manager at Rutgers’ Coastal Ocean Observing Laboratory, helped organize the early network starting in 2007.

In 2009 the U.S. Coast Guard began using that radar data in search and rescue missions, and it’s being applied to oil spill responses too. In time, researchers envision building links for a global network reporting ocean currents.

Supplied by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration through its Physical Oceanographic Real Time Ports System, the harbor data is a newer application of a phenomenon discovered in the early days of World War II – that sea waves would reflect radar signals.

When British scientists turned on their first early-warning system to detect German bombers, “the echo from the sea was a big noise for them,” Roarty said. “They thought the Germans had found out, and were already jamming them.”

In its modern refinement, HF can measure surface currents in the upper three to six feet of water column, up to 120 miles offshore and with at resolutions with detail ranging from 550 yards to almost four miles, depending on the radar frequency, according to NOAA documents.

Worldwide, there are at least 380 networks in 34 nations, with countries like Spain, Thailand and Vietnam buying more HF stations to serve fisheries and search and rescue needs, Roarty said.