Water coming over the bow and downflooding through open, unsecured hatches likely caused the Dec. 8, 2017, sinking of a towboat near Memphis, Tenn., that killed the captain and deckhand, the National Transportation Safety Board reported.

The 66.5’x24’, 1,400-hp Ricky Robinson, operated by Wepfer Marine, Memphis, was manned by pilot Keith Pigram, 35, and his deckhand and stepson Anquavious Jamison, 19, when it capsized and sank at 11:42 a.m. near mile marker 733 on the Mississippi River.

The body of Jamison was recovered when the Ricky Robinson was raised nine days later, but Pigram was never found. There were no eyewitnesses to the sinking, and NTSB investigators reconstructed the sequence of events before the accident from witnesses who had seen the towboat in the minutes before and its last transmitted positions.

The towboat Ricky Robinson sank in the Mississippi River near Memphis, Tenn., in December 2017.Wepfer Marine photo.

At about 10:59 a.m. the Ricky Robinson got underway from the CGB (Consolidated Grain and Barge) Company’s fleet base at mile 730 on the Mississippi, heading upriver toward the Seacor AMH intermodal container terminal about four miles away. The towboat was traveling in lightboat condition without any barges, traveling against a current estimated to be 3 mph to 4 mph.

A pilot who was on the Betsy Ross, another Wepfer fleet boat, told NTSB investigators he saw both engine room doors were open on the Ricky Robinson. The telematic sensor signals from the towboat – similar to the Automatic Identification System – showed it was moving upriver at about 6 mph with Pigram using the twin rudders to steer into the current.

At about 11:25, Pigram made a dramatic turn to starboard, toward the left descending bank, the towboat’s speed decreased from 5.4 mph to 4.4 mph, and then suddenly increased to 7.6 mph. The last telematics signal, transmitted at 11:26:28, showed a speed of 6.5 mph and a position 500 yards from the left descending bank.

The Betsy Ross pilot heard a VHF radio distress call from the Ricky Robinson, with the words “We’re going down.” Seconds later a dispatcher at Economy Boat Store, a fuel service provider at mile 735, received a call from Pigram, who said, “This is the Ricky Robinson. We are in distress. We are one mile down from you and taking on water. Please send someone.”

Both the Betsy Ross and Economy Boat Store workers on their Crew Boat 2 headed to the scene. The Betsy Ross pilot told investigators he saw the Ricky Robinson in the middle of the river “broadside to the flow [current] and heading to the left descending bank.”

The pilot looked down at his own deck to make sure he was not taking water over the bow, and when he looked up again the Ricky Robinson had disappeared. The Economy Boat crew arrived on scene to find debris in the water, and a search effort grew, with Wepfer’s fleet, the Coast Guard, state and local agencies and a state police helicopter joining the search for survivors.

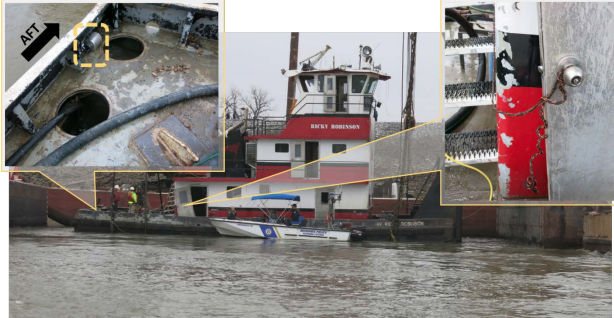

After the Ricky Robinson was raised, only the starboard engine room door was found open, tied off to a stair. Four hatch covers were missing for the port- and starboard-side aftermost and forward stern voids.

Investigators came to focus on water accumulating in those stern voids, after learning from two crewmembers and one former crewmember that stern voids often had to be pumped out if the hatches were not sealed.

During a 2010 drydocking, a window with a downward view was installed beneath the pilothouse main windows so the pilot could watch the deck and see when water was coming over the bow when the towboat was running lightboat. Wepner pilots and company representatives told investigators that when running in lightboat condition, “immediate actions for clearing water from the deck involved backing off the throttles, disengaging ahead propulsion, or in some situations backing the vessel.”

After the towboat was raised, Wepner repaired some $1.5 million in damage and returned the vessel to service. To aid the investigation, the company provided the NTSB with a video of the Ricky Robinson to demonstrate the vessel in a lightboat condition while heading into two different current velocities.

In tests with the boat moving at 4.5 mph against a current of 5.5 mph, and at 6 mph against an estimated 3.3 mph current, water came over the bow rail and onto the forward deck. As the vessel speed increased, the amount of water increased, flowing down the starboard side all the way to the aft deck to the stern voids are located, eventually clearing from the decks through the freeing ports at the bulwark.

The repairs included adding 6” high coamings around the four stern void hatch openings and four dog hatch covers, the report notes.

A submersible pump found outside the stern voids suggested the spaces had not been pumped out since the crew change more than 5 hours, according to the report. The Ricky Robinson was likely taking water over the bow – flowing at a combined speed around 10 mph between the vessel speed and river current – which flowed aft down the deck to open or unsecured hatches, the report says.

With water building up in the voids, the investigators believed, “the pilot’s turn to starboard would have induced a turning heel to port, causing the floodwater in the voids to shift from starboard to port and result in a greater heel to the port side.

“Considering that the water in both stern voids would have substantially reduced the vessel’s aft freeboard, and the turning forces would have caused the deck edge to submerge, additional water likely boarded the aft deck and downflooded into the stern voids, increasing the rate of filling to the voids. As the vessel heeled to a larger angle, water would have also downflooded through the open port engine room door, rapidly flooding the engine room.

“The Ricky Robinson likely then lost stability and quickly capsized, which explains why the Betsy Ross pilot lost sight of the towboat within about 30 seconds. Had the vessel only lost reserve buoyancy due to flooding, it would have taken longer to sink.”

In a memo to the Coast Guard, Wepfer officials had blamed the deckhand for “not keeping the hatch covers tight” and not closing the engine room doors, and blamed the pilot for “producing an excessive rate of speed in a light boat condition.”

“However, former crewmembers stated that the vessel was operated customarily with watertight hatches and engine room doors open despite the company’s checklist requiring closure of hatches,” the report added.

The NTSB concluded that the probable cause of the sinking “was the pilot’s decision to proceed with unsecured deck hatches at a speed that resulted in water on deck and flooding of the aft voids.

“Contributing to the sinking was the company’s inadequate oversight to ensure that crews kept hatches closed while the vessel was under way and that ongoing watertight issues with the voids were addressed.”