Over the past week, the Coast Guard has found itself literally up the river without a paddle.

The Coast Guard caused a firestorm in Congress and among recreational users of the Potomac River when it announced on July 10 that a two-mile portion of the Potomac, a popular spot for Washingtonians to paddle, kayak and canoe, would be closed whenever President Trump and his top aides visit the Trump National Golf Course in Virginia. Parts of the course and its imposing white clubhouse border the river, about 20 miles north of the nation’s capital.

The move angered kayaking and canoeing schools, pleasure boaters, a kayaking program for wounded and disabled veterans, and Democratic members of Congress who protested the closure to Coast Guard Commandant Adm. Paul F. Zukunft after the policy was reported last week by The Washington Post. A week of bad press followed, as radio, TV and newspapers reported on the new security measures and criticized the decision.

Under pointed questions Tuesday at a congressional hearing on Coast Guard resources, Zukunft announced a compromise. He said that he toured the stretch of the river near the golf course by helicopter on Monday, and concluded that “we would strike a balance” between river access and presidential security.

“We’ve listened (to the criticism) and we’re making an accommodation to the public,” he said, adding that the agency has been working with local kayaking and canoeing groups.

The commandant said boaters and paddlers will be allowed to use that stretch of the river by passing through an open channel along the Maryland side of the Potomac, while the river around the Virginia side would be closed.

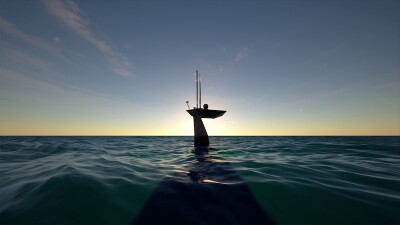

The Coast Guard had proposed closing a stretch of the Potomac River near the Trump National Golf Club in Virginia. Coast Guard image.

The Coast Guard said a full river closure around that location was suggested by the Secret Service and officials downplayed the impact, saying maritime security zones are common when presidents visit coastal or river areas. Coast Guard spokesman David French cited zones set up in Maine, where the Bush family maintains a waterfront home in Kennebunkport, in Hawaii, when President Obama visited, and more currently, at Mar-a-Largo, President Trump’s oceanside resort in Florida. He said disruptions to river users would be minor and brief.

But the reaction was anything but minor and brief, and the Coast Guard did the right thing to quickly address public concerns and offer a partial closure alternative, which was used in the past and was accepted by local boaters as reasonable and fair.

A quick resolution also gives the Coast Guard further goodwill with Congress, which is currently reviewing the service’s fiscal 2018 budget that includes a much-needed replacement plan for the decrepit icebreaker fleet and other aging assets. Sometimes little things can go long way, especially in navigating the swamp in Washington.